Daredevil unicyclists, master illusionists, knife-eating acrobats: Covent Garden’s performers are an institution. They create an extravagant, vaudevillian microcosm, delighted by eager tourists. However, today Westminster Council has launched a public consultation on the future of street performance in Covent Garden and Leicester Square.

Despite weathering a pandemic and adapting to a cashless world, it appears those clowns and magicians are now under threat. In April 2021, a licensing scheme was introduced to regulate performances across the borough. The move has been boycotted by the pro-self-regulation Covent Garden Street Performers Association, or CGSPA, as the group says the rules essentially make their work illegal. After a delayed council vote on Monday, which was aimed at enforcing the legislation, Westminster Council has stepped back from the brink: a public consultation will now be launched, running from January 8 to March 18 next year.

The plan aims to regulate busking and street entertainment in 26 areas of London, ostensibly to “protect residents and businesses from excessive noise and overcrowding”. So far, everything is reasonable. But artists believe the plan has the potential to limit their work entirely and argue that the actual number of noise complaints is minuscule.

The fight for survival

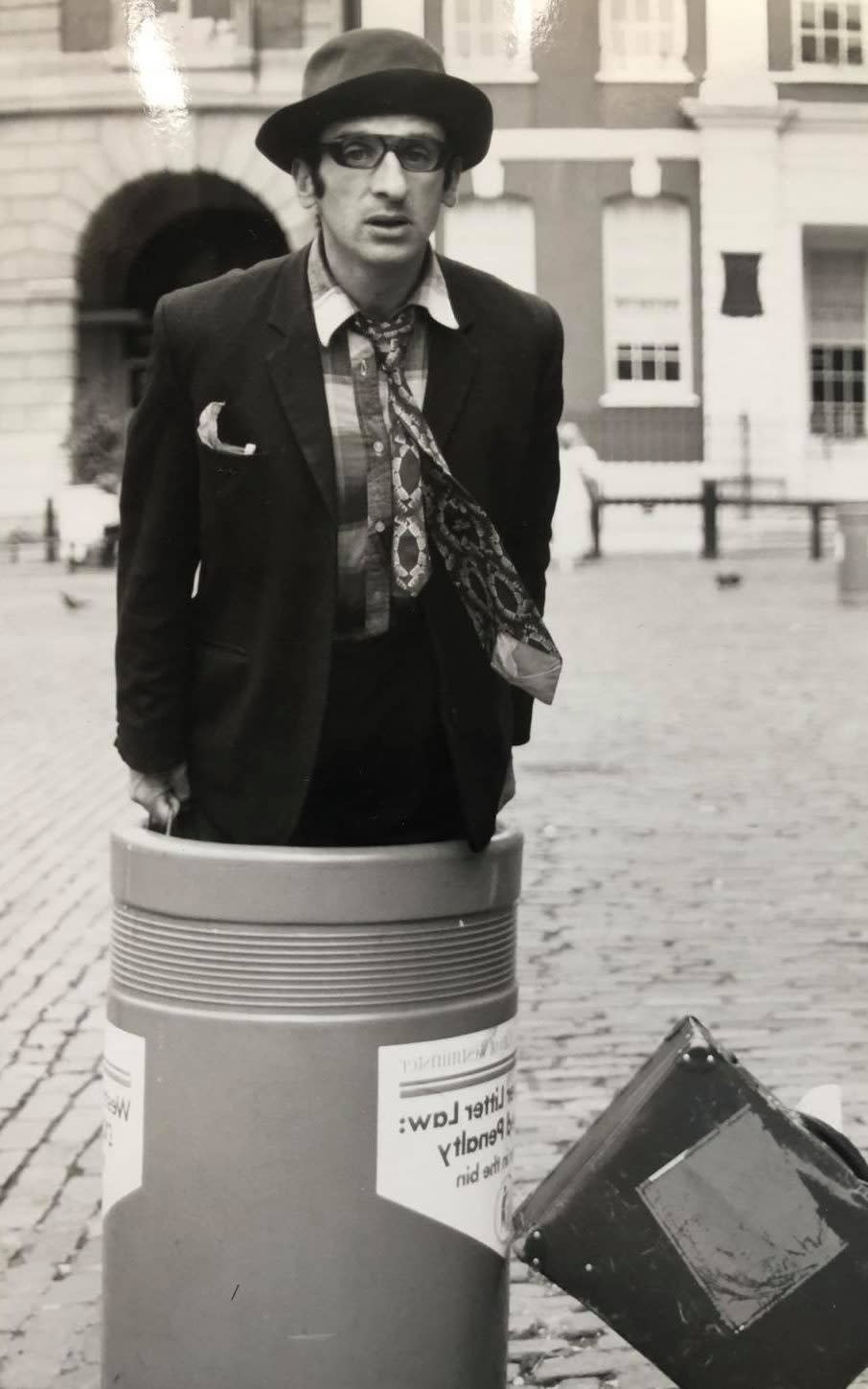

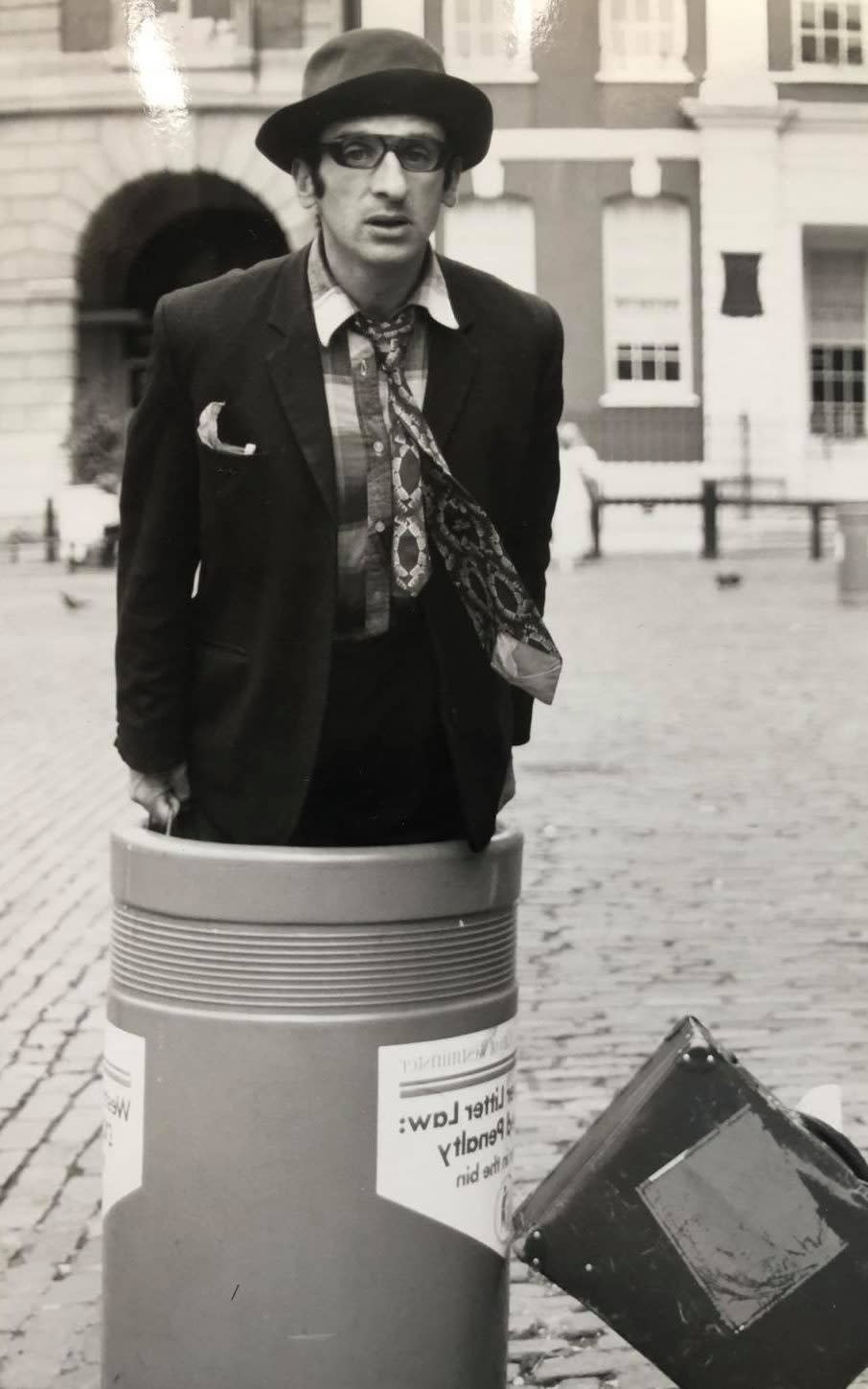

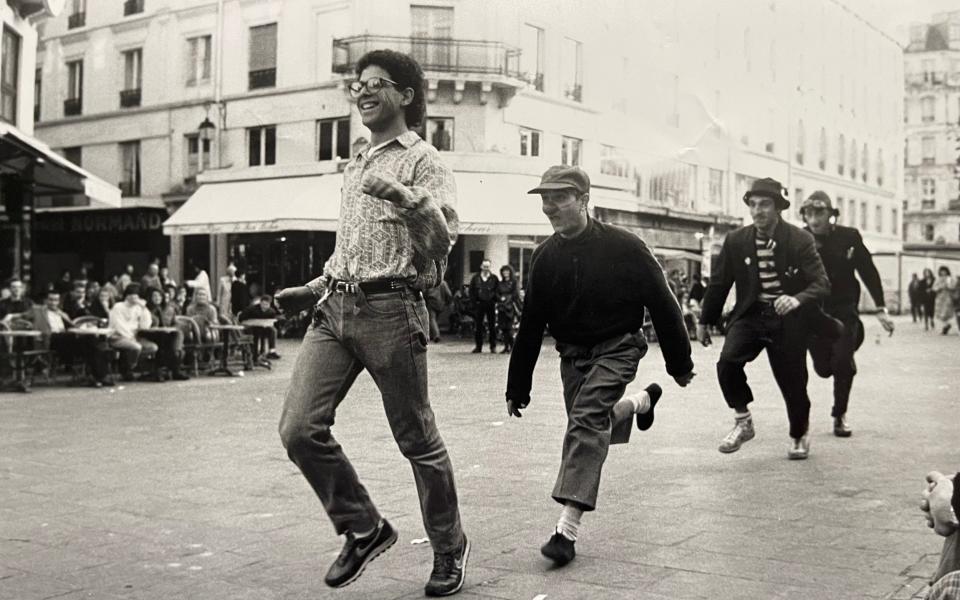

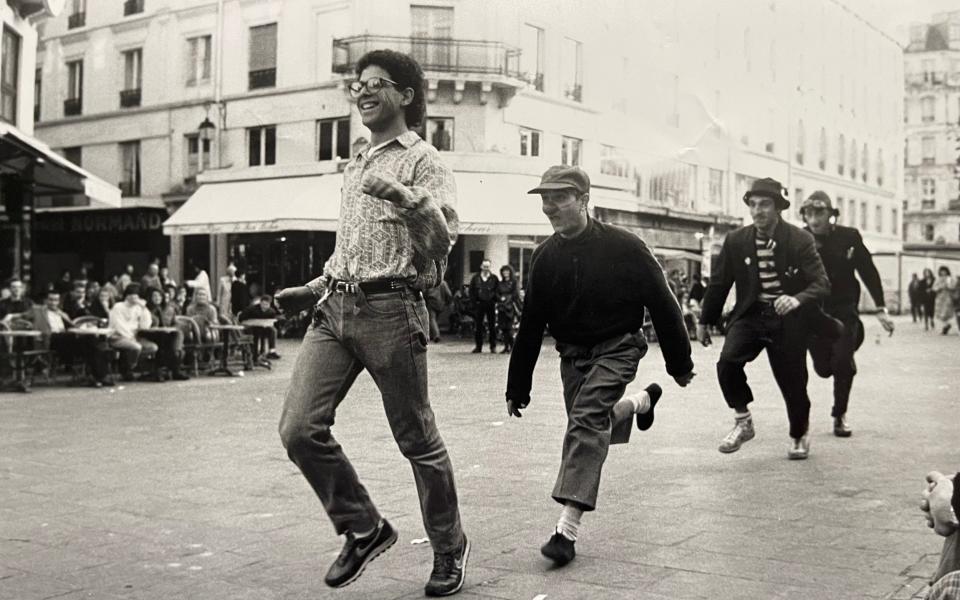

It’s characters like Melvyn Altwarg, a clown who studied in Paris with Philippe Gaulier, who leads the charge. He first performed at Covent Garden in the 1980s and clearly loves the venue. He talks about how he used to gather a crowd by walking in front of groups with a map spread out, standing in their way until they drew enough attention to him. One can imagine the scene: the charming, impish actor, an irresistible combination of the true East End and the theatrical impresario, essentially demanding that people watch him. That mischievous nature persists, but Covent Garden’s international reputation is taken seriously.

“Wherever I’ve traveled (China, Singapore), people have heard of Covent Garden and its street artists,” he says over a steaming coffee, as we shelter from the winter weather in a cafe near the market. “People say to me, ‘Let’s go to London: let’s go to the designer stores and go to Covent Garden.'”

The destination regularly tops lists of London’s most interesting attractions. Pete Kolofsky, a tall, pale, dark-haired performer whose act includes lying inside a “sandwich” of nails, believes the spirit of the place lives or dies with them.

Kolofsky is a “mystery man,” according to Altwarg; With his deep-set eyes and all-black suit, he is certainly stunning. He is also insightful. “The stores may have changed (there are Apple Stores and high-end establishments and everything else), but the real old market remains. That is important for visitors.”

The relationship with merchants, he affirms, is not conflictive. “They come and ask us for change! We help each other,” she insists. “That’s not where the problem is at all.”

Thousands of complaints

It is the noise that seems to particularly worry the city council. In a review of the plan published last June, Westminster City Council said it had received 5,070 complaints related to buskers between April 2021 and May 2023, well above the annual average of 2,200, and more than half of them were related to noise.

In a statement, Cllr. Aicha Less notes that the city council wants to “strike a balance between supporting artists and addressing the problems of excessive noise, overcrowding and unsuitable locations.”

“The council’s licensing committee met on December 4 to discuss options for amending the existing policy. “A ban on busking has never been proposed and will never be proposed.”

It’s not enough for artists. Kolofsky points out that only about five percent of the complaints came from Covent Garden. She bows. “Our own freedom of information requests suggest this number could be even lower,” she adds, with the confidence of a private detective. This, to artists, seems hugely unfair, especially since the restrictions include no flames, knives or sharp objects, no amplifiers powered by generators or, more generally, no “nuisances.”

“We asked for details about which Covent Garden pitch had been the subject of complaints,” he says. “Kerry Simpkin, the council’s head of licensing, specifically cited the Royal Opera ground as the site of greatest local concern. But we know this can’t be true since that site hasn’t existed as a performance venue for almost five years. There are never performances in that place.”

“Like losing an old family”

The group is very much a unified force. On the surface, they seem like a Dickensian motley company. It is misleading and disarming when they talk about business, repeating details of their decision-making processes and management structure. “We have already limited the use of fire, because it is not worth it if something goes wrong. But if all our accessories are banned, we will not have a single act left,” says Juma Kuba.

Artists like Kuba depend on equipment for their shows. Her acrobatic act sees him in a tight leotard, balancing on a stack of cans, themselves balanced precariously on a step ladder. It is flashy and loud: during a demonstration it quickly attracts a crowd. In person, however, she speaks quietly.

He used to work at the Blackpool circus, he says. “When I walked out onto the street, I thought, oh, that’s life. This is where I belong.” Her voice is almost a whisper. “Losing Covent Garden would be like losing an old family photo. Once it’s gone, there’s no way to get it back.”

It is certainly unique. Samuel Pepys’ diary records impromptu street performances in Covent Garden in 1662. However, it was not until the 1970s that its reputation as an entertainment venue was consolidated: in the face of the Greater London Council’s (GLC) redevelopment plans , artistic events emerged. on the site, eventually becoming the “releases” that clowns and magicians now work on.

The artists are clearly in awe of the place. Chris Thomas, with a cigarette between his fingers and an espresso in his hand, says he didn’t know if he was good enough. His act consists of spinning inside a “Cyr wheel,” twisting along the pavement. He is now the picture of confidence, but he admits that he “just fell into it.”

“Covent Garden is the best of the best, though, and I didn’t know if I could do it,” he says, looking at his comrades around the table. It is now her favorite place to work.

Altwarg feels the same. “When he lived in Paris, he didn’t have any money and used to clown around in the streets to save. Once I had money, the first thing I did was run to the bakery and buy a big cream pie. At that time, I couldn’t imagine that I could work here, right in the center.”

Enduring public curiosity

All four say that it is addictive and that it is important for the public to feel that way. “A lot of people who would never have gone to a theater don’t feel like it’s something that interests them,” Altwarg says. “But there is a lot of curiosity: they want to see what this guy is doing with a bed of nails. “They are enjoying something they never anticipated they would enjoy.”

Kuba agrees, saying their programs are, by definition, extremely accessible. They ask the public to give money at the end of their act, but say there is no pressure on those who cannot pay. “After the pandemic, people brought camping chairs to see us,” he says, delighted by the commitment.

His love of performing – and performing at Covent Garden in particular – means that the council’s behavior is interpreted as a personal affront. “It’s misdirection,” says Altwarg, in the language of his actions. “Is!” Kolofsky says. In fact, he says, the licensing system in Leicester Square has meant that noise levels have increased there.

“The artists there think they are playing at Wembley Stadium. “The city council could do something about it, but they don’t.” It is this that makes the CGSPA feel as if it is being attacked, something the council denies.

Kuba says they don’t want to emulate Leicester Square. An ideal outcome would be one that allows the CGSPA to continue with its self-financing system. “We make a profit when an artist has a problem and cannot work; We encourage artists from abroad to come and we learn from each other. “This wouldn’t be possible with the licensing system – we already say that everyone must have insurance, but foreign groups won’t bother applying for a license if they are only here for a month.”

Kolofsky’s outlook is bleaker. “If Westminster Council were successful, the result would be the death of Covent Garden street theatre. “If that happens, then we would have to consider initiating legal proceedings and continuing our fight through the court system.”

If not noise complaints, then what does the CGSPA believe is the real problem? Kolofsky has suspicions about him. “It’s all politics,” he says enigmatically before heading into the snow. He puts on the costume and defiantly exposes his chest and knives on the snow-covered cobblestones.

Altwarg continues to watch. “You know, advice is always about placemaking,” he says. “You can’t do ‘placemaking’ from the top down. “It’s the bases, it’s the artists that create the atmosphere… this is real.”