Some of us don’t watch TV and that’s okay. Some never go to the theater; different hits. Some never listen to music; of gustibus, etc. I? I avoid West End musicals. But show off Never doing X or Y, wearing it as a badge of honor, or declaring the entire art form under the spotlight, is pride of the worst kind of prude. And yet, that’s the opinion you hear about graphic novels.

The problem could be that the form is still very young. Until very recently, it wasn’t unfair to assume that most comics revolved around superheroes and detectives, children’s jokes and talking animals. When did things change? When did people start calling them “graphic novels” and taking them seriously?

Thirty years ago, I think, with Daniel Clowes’s Ghost World, possibly the first naturalistic “literary” graphic novel to become widespread. Some had challenged convention before then: Alan Moore changed superhero stories in his dark satire Watchmen; Art Spiegelman forced us to take the talking animals seriously in the harrowing Holocaust story Maus. But Ghost World didn’t try subvert existing tropes; rather, she blithely ignored them. A novel (and later an Oscar-nominated film) about two cynical girls approaching adulthood in an unnamed American city, it didn’t fall into any of the genre’s obvious silos, and when a novel does that, critics They have no choice but to criticize. Call it “literary.”

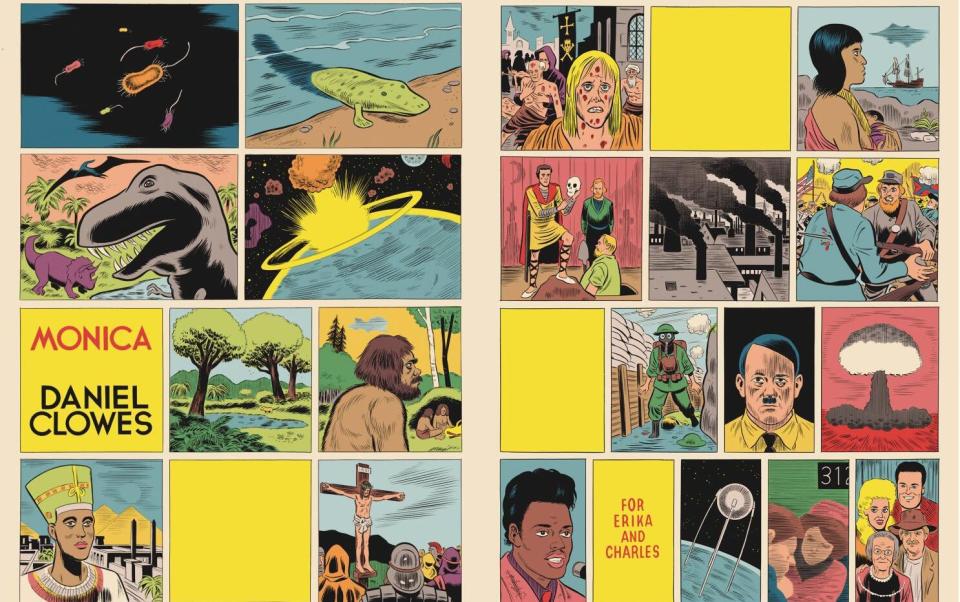

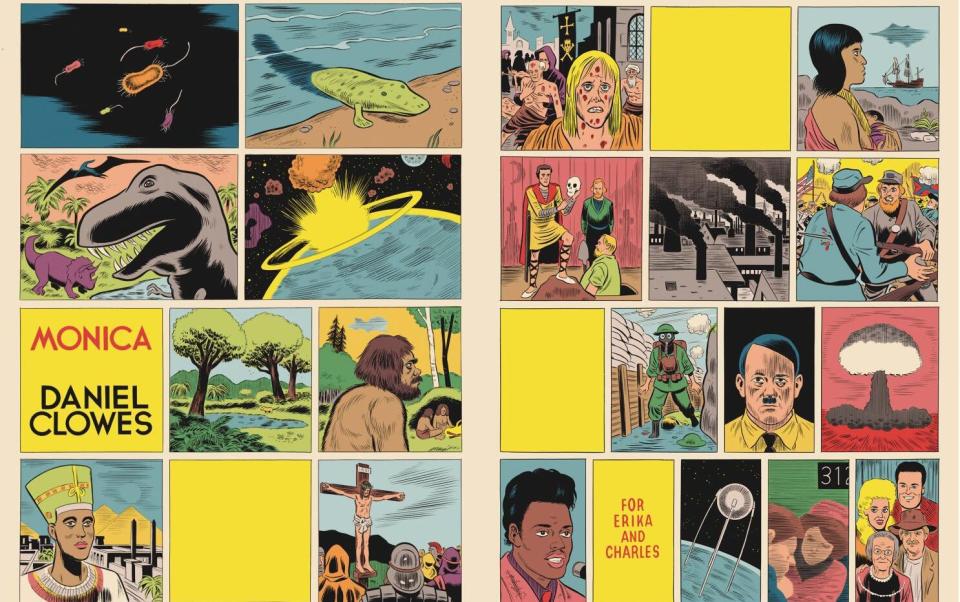

Clowes has already broken seven years of silence with Monica (Jonathan Cape, £20), and turned things around once again. By the last page, you may still be trying to figure out what kind of book it is. is. It’s part a nuanced cradle-to-grave story of a woman, Monica, who longs to know more about her parents, part a critique of empty American ideals from Vietnam to the present day, including the creepy side of flower-power. of the 60s and the cults of the 70s. . (Monica’s hippie mother, who soon disappears, raises her among an “avalanche, an endless cascade of hirsute suitors and strange roommates.”) And it’s partly a love letter to the comic book genre Clowes grew up with, for its artistic style and its rhythm. storytelling to the mottled off-whites of the paper it is printed on, which changes tone from chapter to chapter. (There is a subtle narrative reason for the color coding; no detail in this book is an accident.)

We get a ghost story, supernatural historical fiction, a detective story, a conspiracy thriller: some may be “real”, others may be stories within stories, written or imagined by Monica, whose memories are unreliable. The first chapter, in the style of 1960s war comics, ends abruptly with a soldier’s description of a terrible dream: “The world opens up. Like a wound on the ground.” It plants a seed of Lovecraftian dread that grows throughout.

We can’t resist stories, Clowes suggests; Even a nightmare movie might be more appealing than the idea that life has no meaningful narrative arc, an idea also raised in Emily Carroll’s gothic psychological thriller. A guest in the house (Faber, £18.99), which may or may not be a ghost story. Abby, a housewife in Canada, struggles to love her distant stepdaughter and her dentist husband, but begins to harbor doubts about how his first wife died. Abby’s waking life is monochromatic and bland, but her psychedelic fairy-tale nightmares pulse with blood and neon; she longs to escape to them.

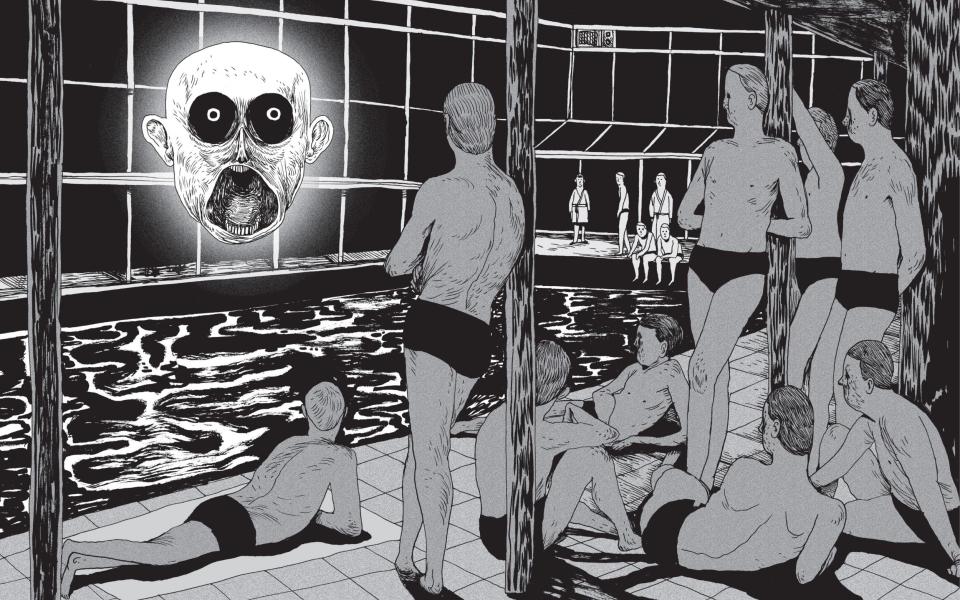

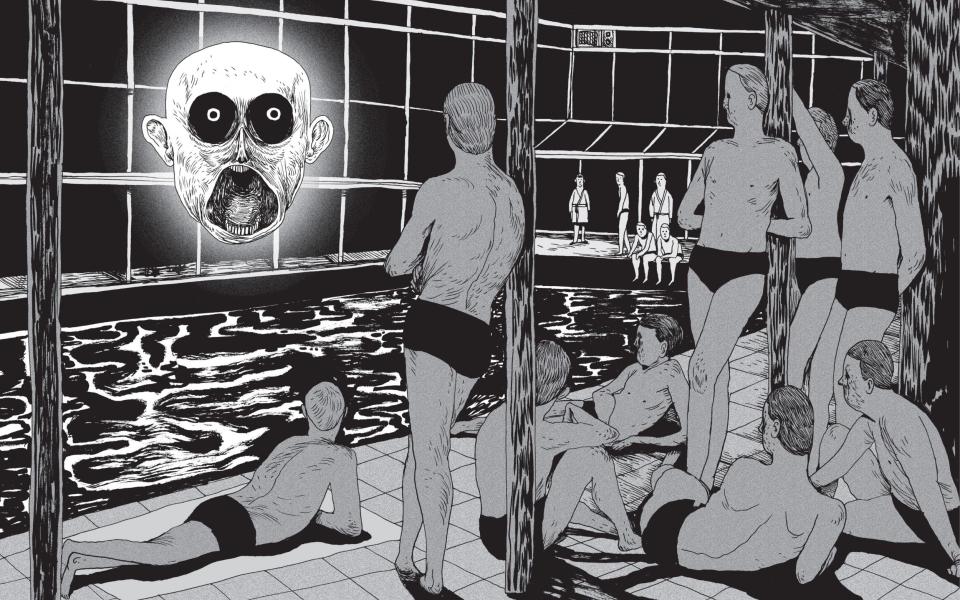

On the contrary, Erik Svetoft’s macabre film Spa (Fantagraphics, £34.99) is all black and white and a nightmare from its creepy first line. An empty-looking man and woman find themselves in an apartment that we later notice is full of dead bodies. “We are living here?” she asks, uncomprehending. “I guess so,” she replies. They chat idly about booking “one of those lovely relaxing weekends”, before moving on to a “lovely” spa hotel. There are luxurious steam rooms and fluffy robes; just ignore the black tendrils escaping from the walls. Genuinely funny and genuinely scary, Spirited Away meets Eraserhead, with a festering dose of body horror.

People who claim that reading comics as an adult is a sign of arrested development…well, they might be right. Many of this year’s most memorable graphic novels have been about children estranged from their parents. Mom and Dad at Paul B Rainey’s Why do not you Love me? (Drawn & Quarterly, £18.99) – drawn like an old Family Circus-style newspaper strip – he can’t remember the names of his two young children and barely bothers to dress or feed them. Why would someone be so horrible? We find. What begins as an absurdist black comedy becomes an allegory for depression and mental illness, and then, movingly (if less convincingly), a love story across different Sliding Doors timelines.

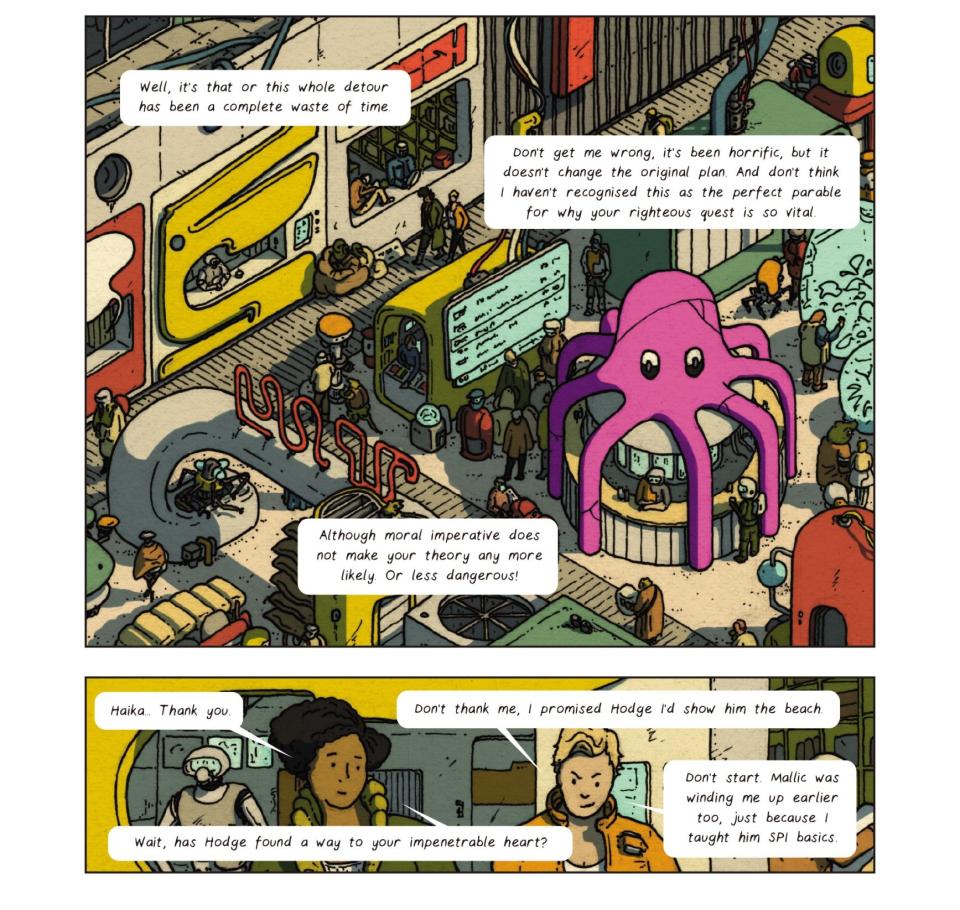

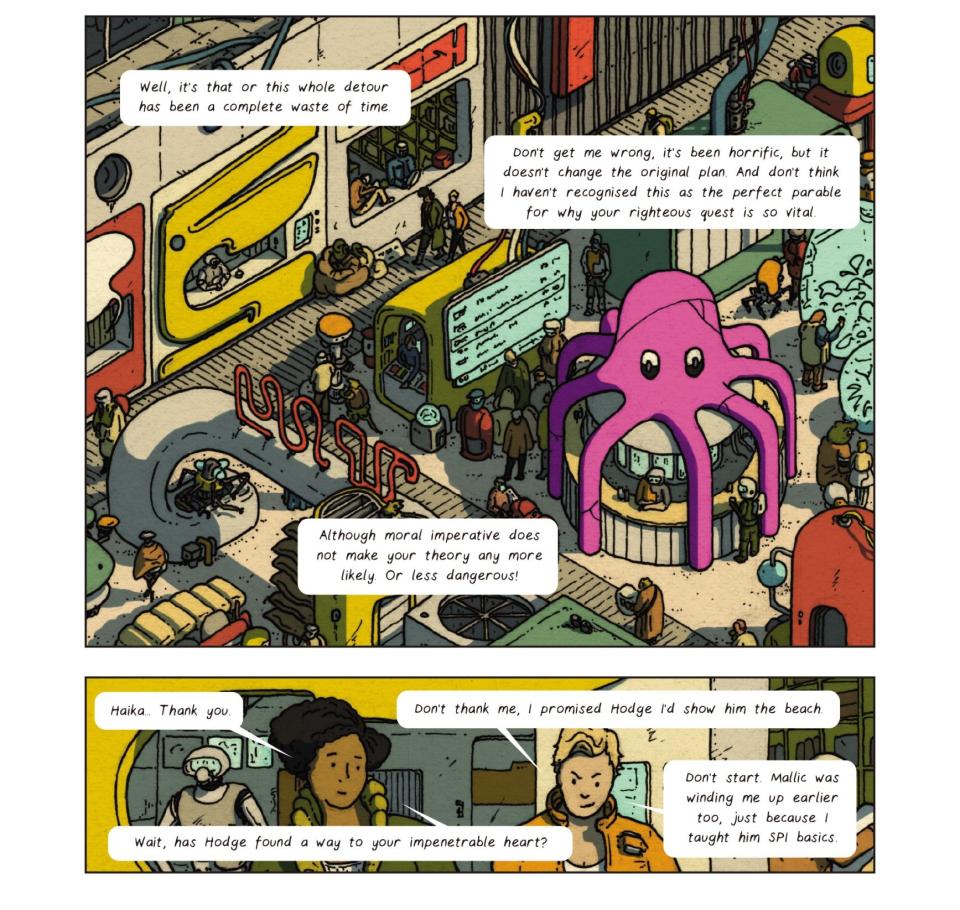

Not all narratives have to be so formally misleading. The fun of architect-turned-illustrator Owen D. Pomery The hard change (Avery Hill, £15.99), in which three explorers make a living salvaging a rare mineral from wrecked spaceships, is straightforward science fiction, halfway between classic Star Wars and the rusty, ramshackle world of Firefly. Pomery’s charming art style is close to Tintin’s clean lines, but with everything slightly wrinkled. I loved him, but he ended too soon and left a dozen threads dangling. Give us a sequel!

Comics have rarely been less comical than the unusually dark vintage of 2023. Half of the ones I’ve read end with an apocalypse, making the ironic understatement of big ugly (Avery Hill, £14.99) even more admirable. She is a bittersweet part of the life of Ellice Weaver, best known for her gorgeous illustrations for newspapers and magazines (including The Telegraph). With a Clowesian balance between vulnerability and sarcasm, she follows a thirty-something brother and sister who find themselves living together after falling out with their father and return to the bickering dynamic of their childhood, as siblings often do. They are catty and kind, hopeless and hopeful, passive-aggressive and occasionally just plain aggressive. Weaver asks whether people can ever really change and wisely leaves the answer up for debate.

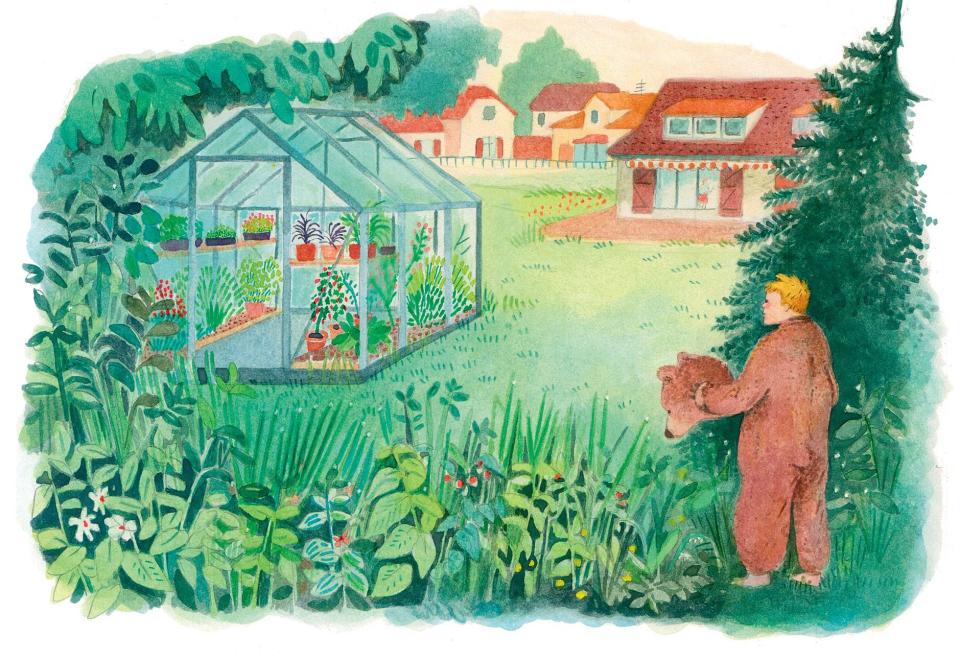

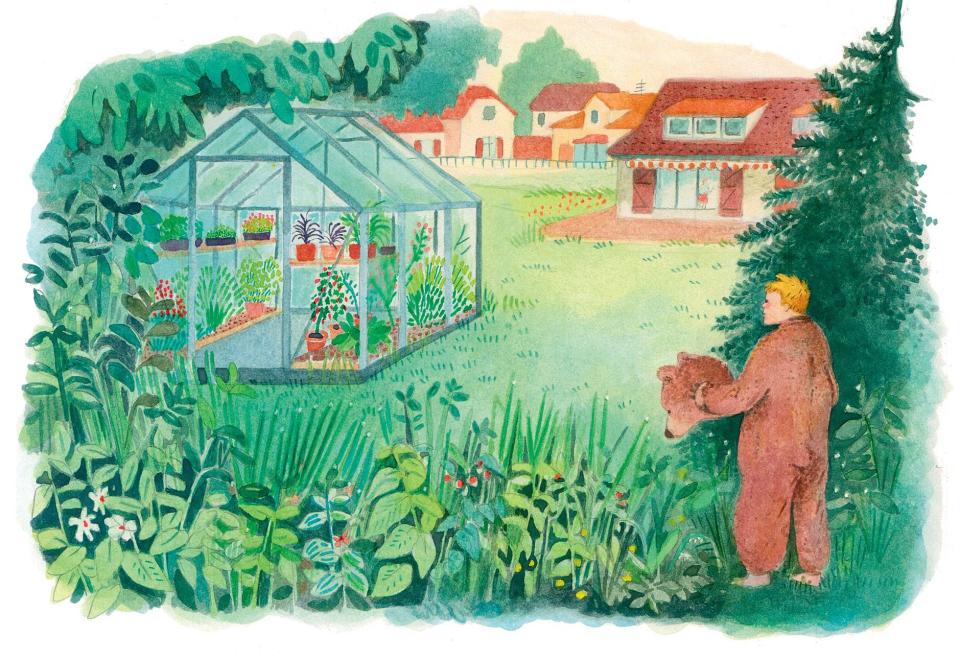

There is a similar gentle restraint in Camille Jourdy’s absolutely lovely voice. juliet (Drawn and quarterly, £23). Anxious Juliette travels from Paris to visit her bickering but loving family in a small French town. We meet a great cast of locals, watch them make love and make flans, and spend the afternoons in a crowded bar. A lonely bachelor adopts a duckling and names him Norberto. He is so pleasantly unhurried; Jourdy devotes entire pages to empty streets in spring, or still lifes where you can almost feel the sunlight floating in the air. And then Juliette leaves. Life goes on. If you think comics aren’t your thing, this one might change your mind.

To order these books at a reduced price, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph books