It has been suggested that Mickey Mouse was, along with the Coca-Cola label and the swastika, the most recognizable symbol in the world. The indefatigable rodent made his first on-screen appearance in the 1928 animated short Steamboat Willie, which, thanks to a quirk of copyright law, enters the public domain on January 1, 2024. Still, good luck for those who now believe they will be able to capitalize on Mickey’s character.

Walt Disney, whose company owns (and indeed exploits) the mouse, long ago trademarked it and secured its copyright. So while the original, black-and-white Mickey Mouse may now appear in a variety of forms, the best-known version of him will, in the words of an admittedly testy Disney spokesperson, “continue to play a leading role as an ambassador Global Walt Disney Company.

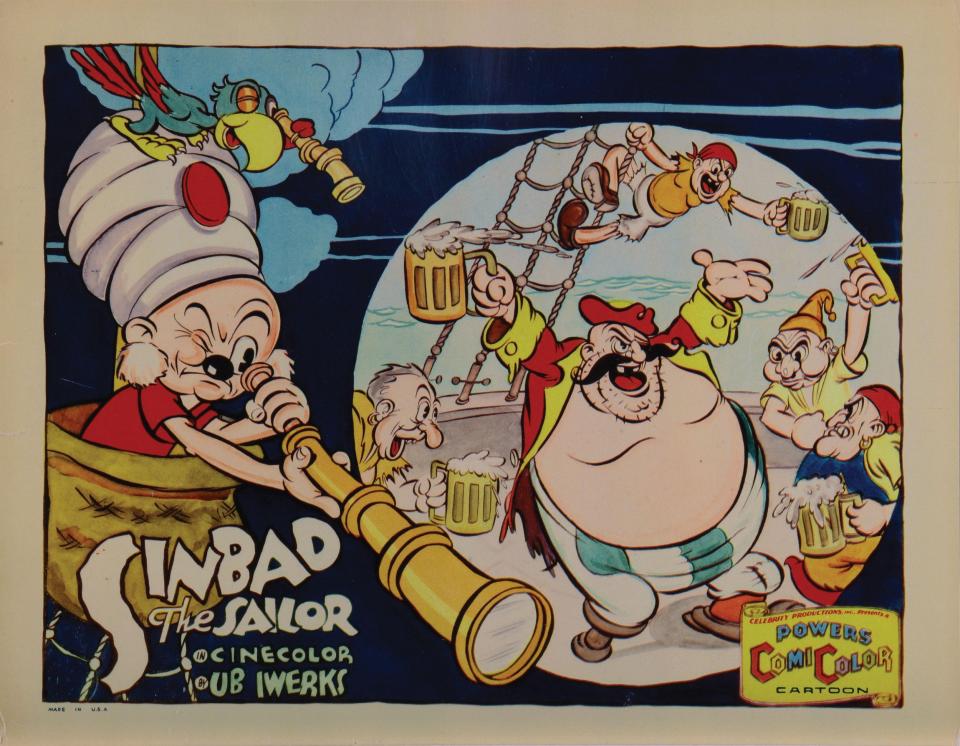

Those of us who are happy that a multi-million dollar company can continue to make money hand over fist thanks to its most popular character will no doubt breathe a sigh of relief at this news. However, Steamboat Willie’s appearance in the public domain should draw attention to one of the great unsung figures of the ’20s.th Animation of the century. Ubbe ‘Ub’ Iwerks not only worked alongside Disney in the early days of his empire, but he was responsible for designing the character of Mickey Mouse.

Although he hasn’t exactly been erased from history, Iwerks’ much lower profile compared to his colleague and employer shows how brutally skilled a myth-maker Disney really was. The story we are left with is a sanitized (even Disneyfied) version of what really happened.

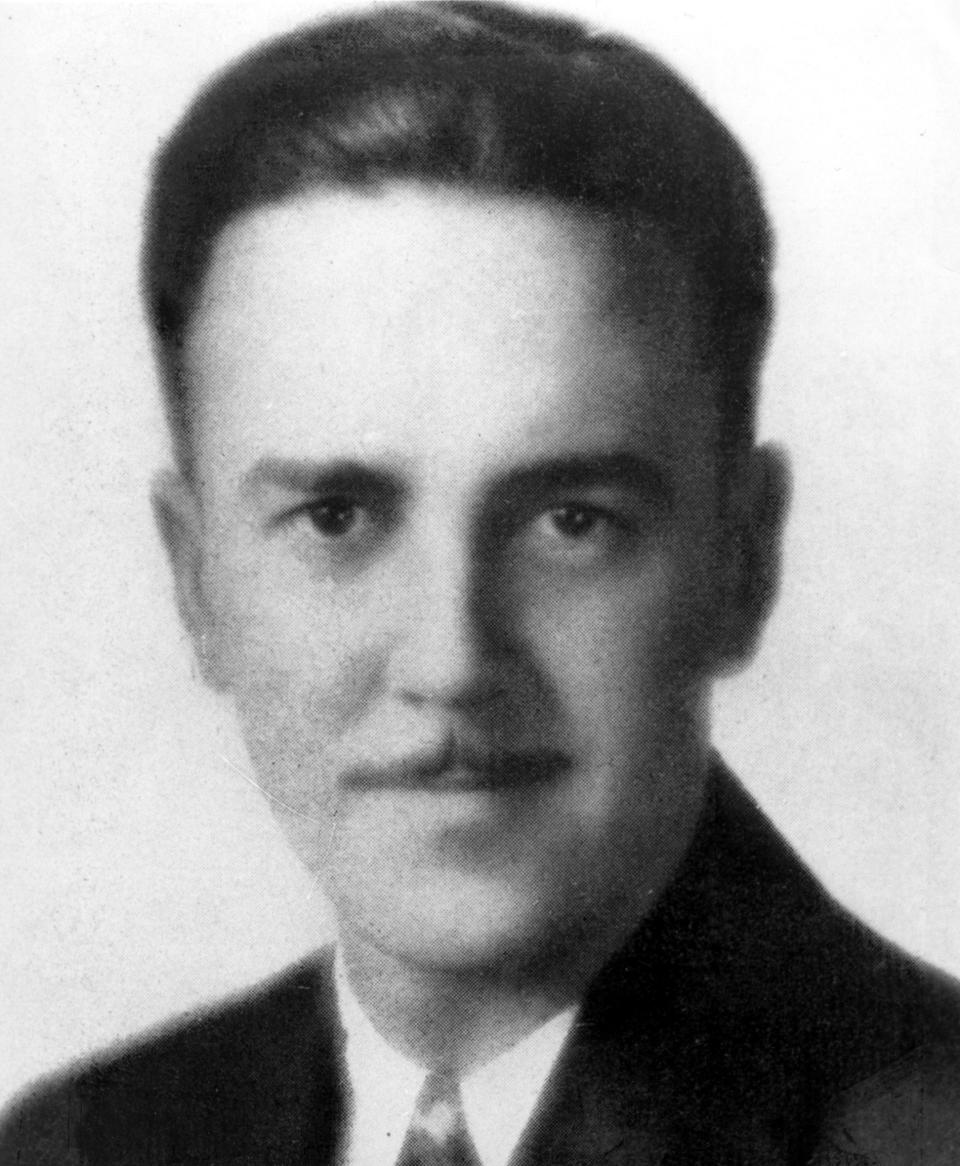

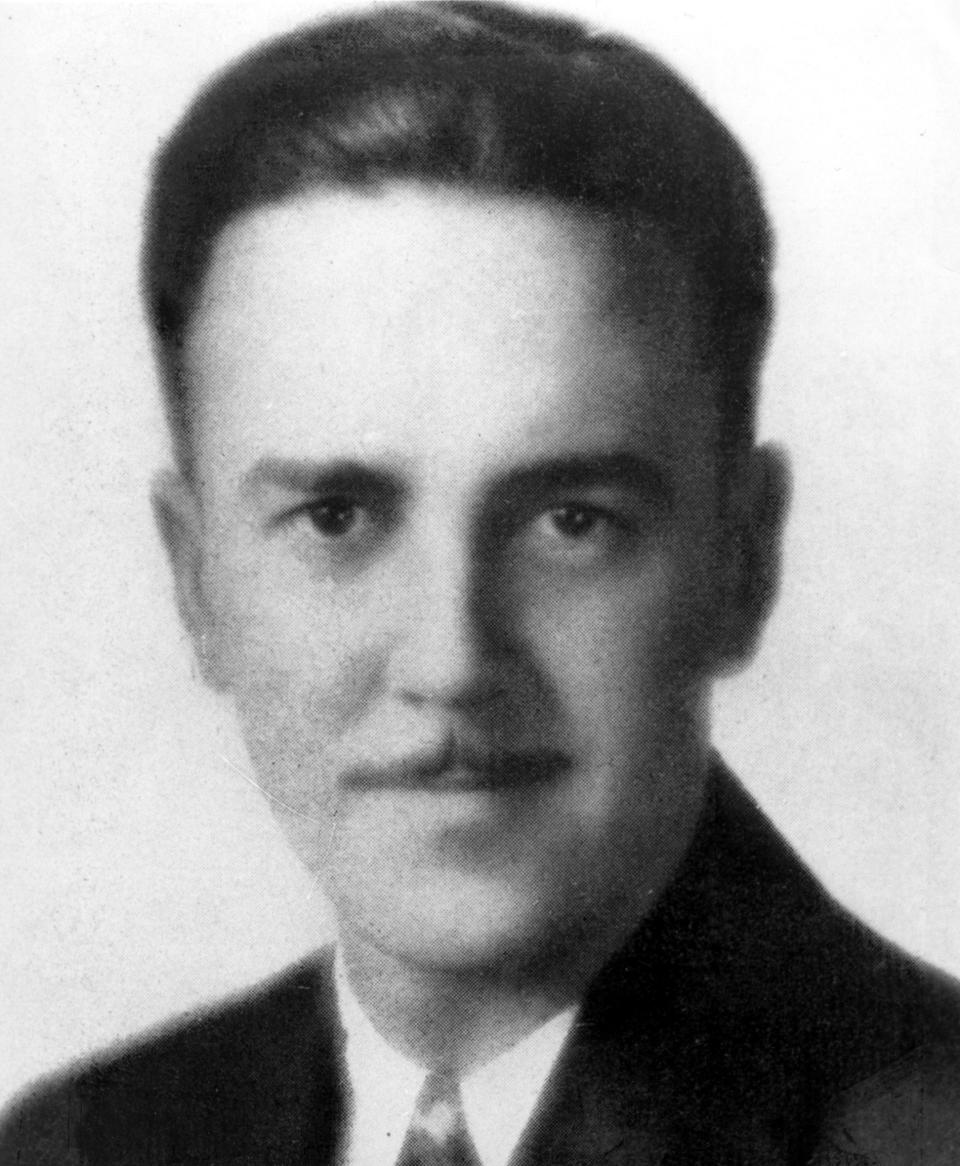

Iwerks, the son of a traveling Dutch barber whom he hated (upon learning of his father’s death, he sneered, “Throw him in a ditch”), first met Disney when the two men were teenagers working at the film company. Kansas City, Pesmen. Rubin Art Studio. The core differences in their personalities could already be discerned. Iwerks was an enormously talented workaholic who, if necessary, could do two months of work in two weeks, illustrating hundreds of animation cells by hand each night. Disney, while also a skilled animator, excelled at the corporate side of the business.

The two collaborated during the 1920s, with Disney largely the primary partner. But when they moved to Los Angeles in 1923, their careers hit a roadblock when Universal Studios, the production company that owned the film rights, snatched away the first cartoon character they co-created, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. him. An outraged Disney vowed not only to retain all rights to the characters for which he was responsible, but also to create a figure who would be considerably more successful – and iconic – than Oswald ever was.

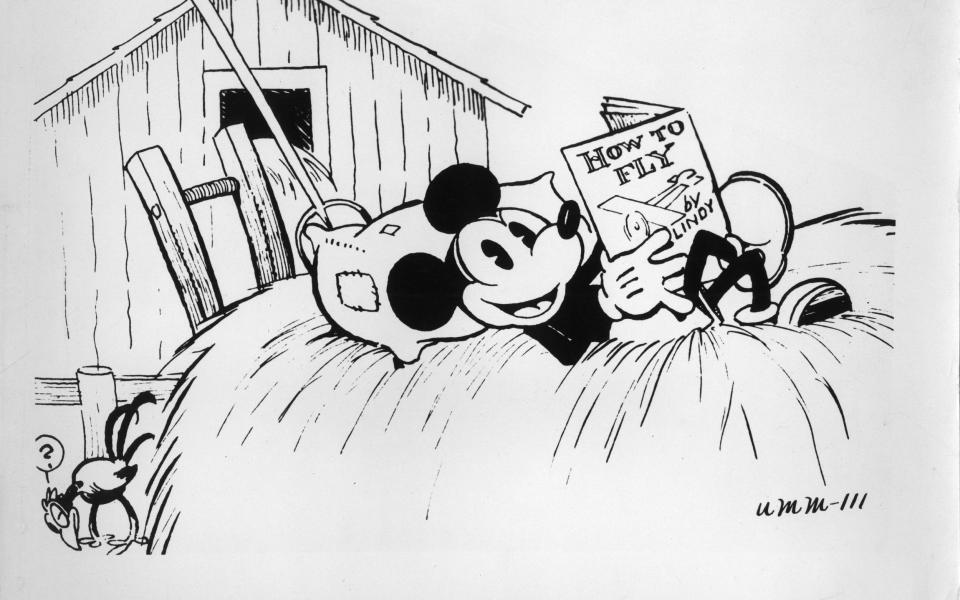

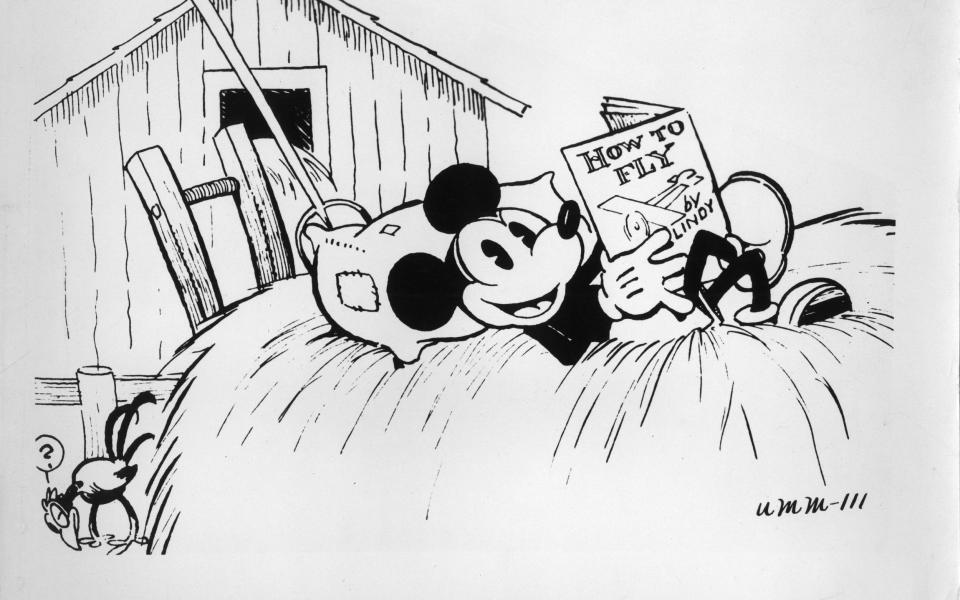

The story of how Mickey Mouse was created was one that Disney liked to tell in his old age, in folksy, exaggerated detail. He claimed that he came up with the idea for an anthropomorphic mouse on a long train ride from New York to California, or that he was inspired by a pet he had during his days in Kansas City. Both, or neither, could be true.

But what is indisputable is that Iwerks came to Disney’s rescue when it ran out of a character it could monetize, and that, between the two of them, they came up with a figure that was originally called Mortimer Mouse. Until Lillian, Disney’s wife, didn’t like what she considered too pompous a name and she suggested changing Mortimer to Mickey.

There’s no doubt that Disney invested a lot in the character, especially since he voiced him for years, and was responsible for creating the quirks of Mickey’s personality that largely led to him becoming the much-loved character he still remains today. today. . However, the rush to claim credit meant that Disney inadvertently or deliberately left out Iwerks’ work in coming up with Mickey Mouse’s iconic design.

For a long time, Disney assumed ownership of the character, and today the accepted party line is that, in the words of one Disney employee, “Ub designed Mickey’s physical appearance, but Walt gave him his soul.” However, this is an inaccuracy. As Iwerks biographer Jeff Ryan has commented: “[Iwerks] He was the person who was doing most of the work behind the scenes. And when Walt was taking credit, it was Ub who was denied credit. Walt, never satisfied with anything, continued to make up bigger and bigger lies to expand the story of Mickey Mouse’s creation. And the worst thing at first was that Walt was the one who did it. He did not do it”.

The reasons for this are more complex than they seem and, as Ryan has suggested, “when you put Walt and Ub together, they were capable of doing almost anything.” However, Iwerks quickly tired of the Disney spectacle and being treated like a junior partner. Their working relationship came to an end in 1930, when – apocryphally – Disney, when asked at a party by a young admirer to draw him a sketch of Micky Mouse, simply handed Iwerks a pen and paper and told him, “Draw it.” Cue a furious Iwerks storming out of the party and starting his own animation studio, Iwerks Studio. (He was paid less than $3,000 for his 20 percent stake in the company, a stake that today would be worth billions.)

In an ideal world, this would have become a rival to Disney, perhaps even replacing it. But Disney knew the importance of hiring talent and that’s why it surrounded itself with young, capable animators. (Although Iwerks was responsible for discovering Chuck Jones, the man who would later create the Looney Tunes cartoons.) Iwerks struggled to make his way on his own terms during the 1930s, and in 1940 he returned to Disney. Only this time he was not an animator, but a visual effects supervisor: a recognition that the only way the working relationship between the two men could resume once again would be if Iwerks were doing something new and different from the previous efforts of he.

For the next 25 years, Iwerks worked tirelessly and fruitfully at many of Disney’s companies. He was responsible for pioneering the integration of live action and animation on screen, which he first attempted in the much-maligned 1946 musical drama Song of the South and then, much more notably and successfully, perfected in the Disney’s momentous hit, Mary Poppins.

He also worked on Disney theme park attractions, designing shows such as The Hall of Presidents and the It’s A Small World attraction. Demonstrating his virtuosity, he left Disney to design the terrifying special effects of Hitchcock’s The Birds, for which he was nominated for an Oscar (he had already received a special Academy Award in 1960 for “the design of an improved optical printer for visual effects.” specials and mate shots.”

Animation genius, special effects pioneer, theme park visionary: Ub Iwerks should, by rights, be as remembered as Disney, Jones or any of the other leading figures in 20th century entertainment. The fact that he is not may be due to Disney’s desire to exclude him from credit for his achievements (although he was named a Disney Legend in 1989, following his death in 1971), but also to his unease. .

He loved taking a car apart and putting it back together in a weekend, and was known for building cameras from parts he found lying around his garage. He took up archery, but gave it up after getting bored of hitting the target over and over again. And as Ryan said of Iwerks: “There’s a famous story in animation circles about Ub Iwerks’ brief love of bowling. He got better and better until one day he threw 13 strikes in a row. And as soon as he did that, he said, okay, I solved the bowling. And he never bowled again.” (The same could be said of his early career at Disney, in which he excelled in both innovation and trend-setting animation, before leaving behind his unbroken record of strikes, never to return.

The treatment of Iwerks may be a nearly forgotten incident in the Mouse House, but it remains common knowledge in popular culture circles. The 1996 Simpsons episode The Day the Violence Died revolves around a homeless man, Chester J Lampwick, voiced by none other than Kirk Douglas, who tells Bart that he is responsible for the character’s creation. Itchy the mouse from the show Itchy and Scratchy. Roger Meyers Sr. forced him to resign and denied him royalties, a not-so-subtle dig at Disney, even down to a joke about cryogenically freezing him. Lampwick ultimately triumphs and receives an $800 billion settlement that bankrupts Meyers’ son and results in the termination of Itchy and Scratchy.

However, the most revealing moment of the episode comes when Meyers declares in court that “Animation is based on plagiarism! If it weren’t for someone who plagiarized The Honeymooners, we wouldn’t have The Flintstones. “If someone hadn’t scammed Sergeant Bilko, there wouldn’t be a Top Cat.” And, the episode might have added, if there hadn’t been Ub Iwerks, there wouldn’t have been Mickey Mouse and there probably wouldn’t have been the Disney empire as we know it today. So if Steamboat Willie’s entry into the public domain makes the Iwerks name better remembered, this can only be a good thing.