Thirty-six years ago, when Mike Gunton joined the BBC’s Natural History Unit as an enthusiastic young producer at the start of his career, he was told he would be working on David Attenborough’s final show. He was The trials of life, a study of animal behavior, and Attenborough, then sixty years old, thought it was time to stop. “Well, that seems pretty funny now,” Gunton says. “I don’t know how many series he has done since then, but there must be at least 20. May it last a long time.”

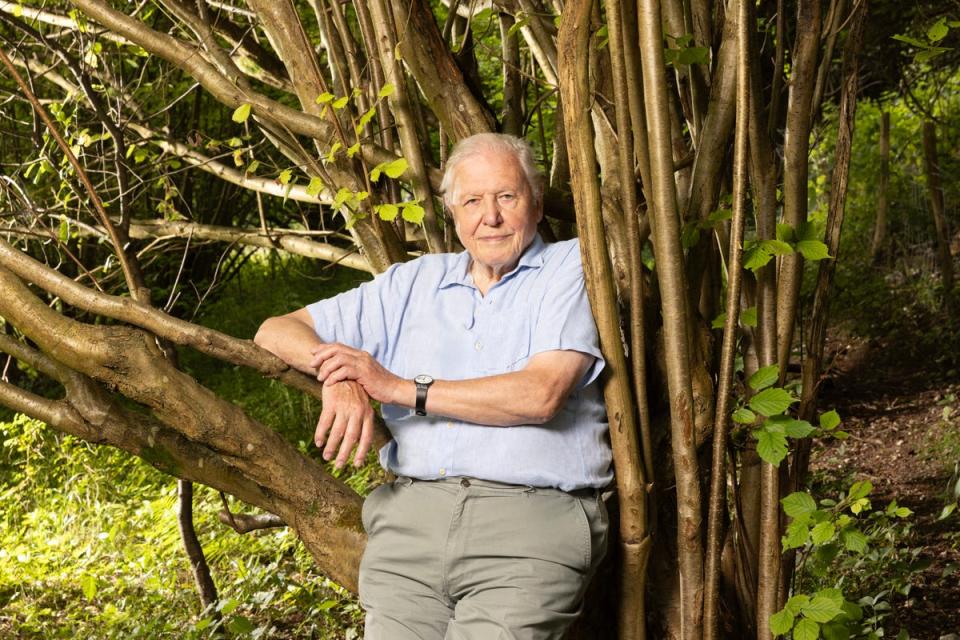

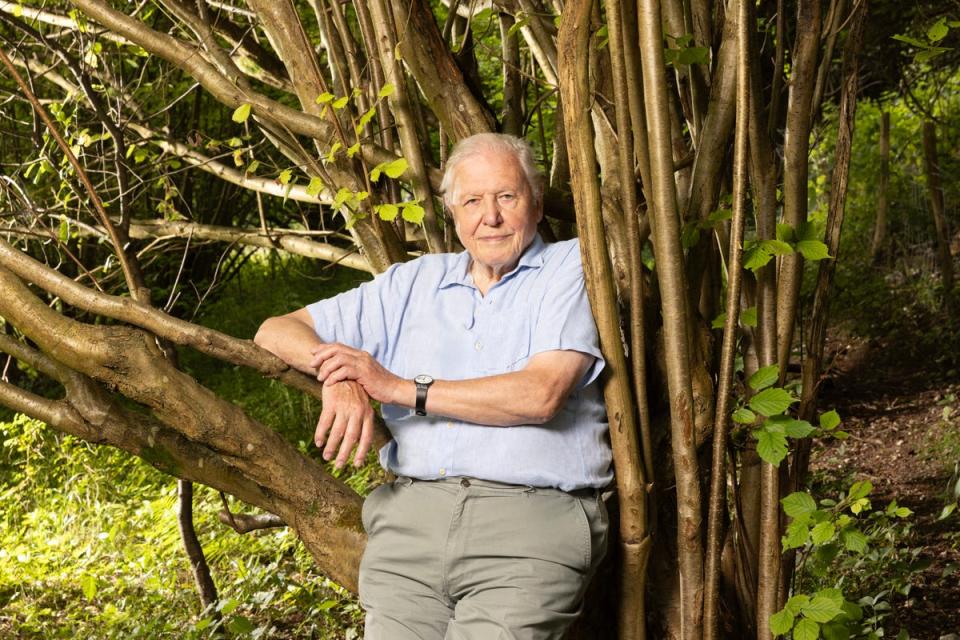

The pair have worked together for almost four decades (Gunton is now 66 and Attenborough is 97) and their latest project is Planet Earth III, which airs its final episode tonight. Like its two predecessors, which aired in 2006 and 2016, the series has shown us spectacular stories from across the animal kingdom: from a minute-old baby ostrich searching for its mother in the Namib Desert to a group of brave seals moving away. great white sharks off the coast of South Africa. But a new element of the show, and one that is increasingly present in Attenborough’s other shows, is its message: this series is about how animals are forced to adapt to survive the challenges they face in a changed world. By humans.

“I’ve done a lot of shows in my life,” Gunton says, “but this is definitely a big one. It still feels like we’re getting the Planet Earth tingling, in the sense that it gives us wonderful things about nature, but we are also saying something about being sensitive to how much we step on our planet.” Planet Earth III This certainly demonstrates our negative impact on animal life (turtles on Australia’s Raine Island, for example, are dying en masse as temperatures rise). However, it also shows how we are innovating to improve things (while the right whale was hunted to near extinction 40 years ago, the ban on commercial whaling has restored its numbers to around 12,000). “It’s a very intriguing time to be looking at the natural world right now, and it’s also a little worrying. But there are parts that give you hope and that has to be reflected in the programs.”

In some ways, a lot has changed since Gunton and Attenborough began working together. Attenborough wasn’t a fan of drones when they first appeared on the scene. They would constantly fail and he would have to take countless shots walking through a meadow or jungle while the drone camera zoomed out to reveal him in place. “He is now a convert and absolutely believes that the drone is the key, the breakthrough, in the perspective that he can give about what is happening in nature,” Gunton says. Technological advances have been enormous over the decades. “He’s amazed at the leap we’ve made in the way we use robotic cameras,” adds Gunton. “We can take audiences beyond what the human eye can see.”

If someone ever asked me, “What are your memories of him?”, one of the best things I would say is that we laugh, sometimes about the absurdity of the world and the absurdity of what we do.

In other respects, nothing has changed at all. Attenborough has always had “a penchant for bird courtship stories” on his shows, and he always will. “There is a sequence in Planet Earth III with the Tragopan, which is a very strange bird that lives in China and has a very complex and strange courtship,” says Gunton. “I don’t think it’s ever been filmed in nature. And of all the things we showed David, it was the one that made his eyes light up.” And Attenborough has always been “hilarious,” Gunton says. “If someone ever asked me, ‘What are your memories of him?’, one of the best things I would say is that we laugh, sometimes about the absurdity of the world and the absurdity of what we do. He is a brilliant storyteller.”

Gunton too. We went well beyond our schedule on Zoom and I can say that I would be happy to tell stories about his and Attenborough’s adventures for hours (I heard that he sent Attenborough to battle with warrior termites in Nigeria, and the two of them were sitting, surrounded by butterflies in Downe Bank Nature Reserve in Kent). Gunton didn’t always think he would go into natural history (he initially wanted to be a social documentary filmmaker), but during his time as a zoology student at the University of Bristol, a paleontology professor took him under his wing and he became a “obsessive student.” After going to Cambridge to do a PhD in zoology, he returned to Bristol to work at the BBC’s Natural History Unit, where he is now creative director.

He says that, over the years, Attenborough’s “curiosity has remained absolutely boundless.” When Gunton visits Attenborough’s home in Richmond, “there will be a stack of books on the piano that he will be reading, while he reads them. He’ll say, ‘Have you read this? Have you seen this?’ It’s that kind of constant scholarship. He is very busy. It’s crazy. He is at this event and that event and in some library here, and the energy is amazing.”

He tells me a story to prove it. During the filming of The green planet, that came out last year, there was a sequence in which Attenborough gave a presentation from a rowboat on a lake in Croatia. Gunton, three decades younger than Attenborough, had to row most of the time when the cameras weren’t rolling, but Attenborough wasn’t having it. He jumped into the rowing seat at the first opportunity. “I’ll row. No, no, I will. I’ll do it,” Gunton remembers insisting. “We started to be competitive because he was a rugby player in college. [in Cambridge] and I also. She was saying, ‘Look, come on, I’m a rower.’ He said: “No, we rugby players can row as well as you.” So when he was 94 years old, he basically rowed that boat about a mile, and it was a big, heavy boat. Working with him at ninety years old is not that difficult, because he can do almost anything.”

While Attenborough tends to take the field less and less these days, Gunton says his influence on the series goes far beyond his storytelling. “This has been his format, since he made Life on Earth [in 1979]. So these shows are effectively tweaking or circling the edges of that format, with their DNA there all the time.” Gunton says that with every take, every story in the series, he thinks, “How is David going to tell this?” He will also exchange ideas with Attenborough and seek advice from him on more complicated scenes.

Attenborough is the man to ask. He has been the biggest influence on nature programming forever. His hilarious storytelling has us captivated by the antics of everything from thin weeds on the ground to little sea angels in the ocean. Seeing nature in this impressive way has taught us all about the wonders of the world and the need to protect them. And many others – most recently Morgan Freeman, who presented the inferior Life on our planet on Netflix – they have failed to replicate its magic.

The last time Attenborough was properly in a series, going on intense expeditions, was for The green planet. “We went to Costa Rica, across America and to the deserts of Central and South America,” Gunton says. “And we went to the outskirts of the Arctic Circle in Finland and to Slovenia. He loved it. Before, we were talking about how many days we would have and we said, you know, maybe three weeks or something in total. And his daughter was there, with whom he works a lot, and she told me: ‘Look, you have to be careful, don’t do too many days.’ And when she left to go make us a cup of tea, he turned to me and whispered, ‘Actually, let’s wait a couple more days!’ Actually, that sums it up. He was 94 years old.”

Gunton struggles to imagine a future without Attenborough guiding us through the natural world. “Forty years ago, I was a new kid in the Natural History Unit,” he says. “And they said, ‘Of course, this is David’s last series, so we should be thinking about who’s going to take over.’ And that’s something people have been talking about ever since. I think it’s one of those things where we cross that bridge when we come to it, but at the moment, it looks like it’s going on six cylinders.”

He laughs and admits that he “shamelessly” asked Attenborough if he would ever retire. Attenborough’s response? “That does not mean that word”.

The final episode of ‘Planet Earth III’ will air at 6.20pm on BBC One on Sunday 10 December.