Like most kids of the 1990s, I attended a school that used the original DARE program as a key initiative in the war on drugs. Congressional funding for this Drug Abuse Resistance Education program increased to more than $10 million a year in 2002, even though studies published in the previous decade showed that the original program was ineffective in preventing use. of substances. Following growing political pressure and declining government investments, the DARE program was reorganized.

This scenario exemplifies how a disconnect between research-based information and decision-making can lead to ineffective policies. It also illustrates why scientists often complain that it can take more than a decade before their work achieves its intended public benefit.

Researchers want the results of their studies to have a real-world impact. Policymakers want to formulate effective policies that serve the people. The public wants to benefit from tax-funded research.

But there is a disconnect between the world of science and the world of political decision-making that prevents information from flowing freely between them. There are hundreds of evidence-based programs that receive minimal public investment despite their promise to curb social ills and save taxpayers money.

At Penn State’s Research Translation Platform, I work with a team that studies policymakers’ use of research evidence. Lawmakers and other decision-makers tend to prioritize certain solutions over others, largely based on the type of advice and input they receive from trusted sources. My team is developing ways to connect policymakers with university researchers and studying what happens when these academics become trusted sources, rather than those with special interests who stand to benefit financially from various initiatives.

Build relationships between researchers and policymakers

Our Research Translation Platform team has found that policymakers assess how credible a person is in different ways. University researchers are generally considered more trustworthy and impartial than special interest groups, lobbyists, and think tanks. Academic researchers can be key, trusted messengers, and their information is most credible when it does not advocate particular political agendas.

But scientists and policymakers don’t usually have quick contact with each other. Making these connections is a promising way to improve policymakers’ access to high-quality, credible information.

Based on these principles, I co-developed a service that connects state and federal policymakers with researchers who share their interests. Called Research-Policy Collaboration, it involves a series of steps that begin with identifying policymakers’ existing priorities (for example, addressing the opioid crisis). We then identify them and match them with researchers working on studies relevant to substance use. The ultimate goal is to facilitate the meetings and follow-up that are essential to developing mutually beneficial partnerships between policymakers and scientists.

Working closely with prevention scientist Max Crowley, we designed the first experiment of its kind to measure whether our model was useful to congressional staff. We found that legislators we randomly assigned to receive support from researchers introduced 23% more bills that reference research evidence. Their employees reported that they valued using research to understand problems more compared to employees who were not paired with a researcher.

This experiment demonstrated that partnerships between researchers and policymakers can be effective not only in bridging research and policy, but that legislators and their staff can find value in the service to refine empirical evidence related to their bills.

Put research in the hands of policy makers

While research-policy partnerships can be effective, they are also time-consuming.

When the world was turned upside down by the COVID-19 pandemic, routine handshakes disintegrated into social distancing. As a flurry of activity in Congress attempted to sort through the catastrophe, pandemic conditions provided an opportunity to experiment with a way for researchers to communicate directly with policymakers online.

Our team created what we call sciComm Optimizer for Policy Engagement, or SCOPE for short. It is a service that directly connects legislators with researchers who study current political issues. Researchers write a fact sheet in their area of study summarizing a set of research related to a national policy issue.

The SCOPE team then sends an email on your behalf to legislators and staff assigned to the relevant committees. Email invites the opportunity to connect further. This effort is more interpersonal than a newsletter and provides a direct connection to a trusted source of science-based information.

As part of this effort, scholars produced more than 65 fact sheets, as well as several virtual panels and briefings relevant to various policy areas during the pandemic, such as substance use, violence, and child abuse. These were disseminated over the course of a year and typically led to two meetings between researchers and policy makers each.

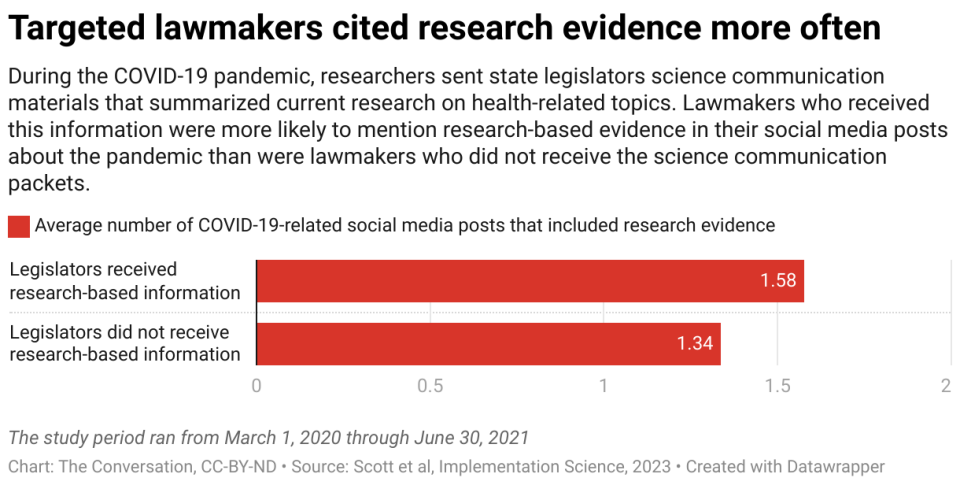

To investigate the value of this service, we analyzed the language state legislators used in social media posts related to COVID-19. We found that those we had randomly assigned to receive our SCOPE emails produced 24% more social media posts referencing research than those we did not contact. In particular, we noticed increased use of technical language related to data and analytics, as well as more language related to research concepts, such as risk factors and disparities.

Policymakers who received SCOPE materials also used less language related to generating more or new knowledge, suggesting that they were less likely to request more studies to produce new evidence. Perhaps his access to evidence lessened his need for more.

Leverage timely and relevant research

These studies show some promising ways to connect policymakers to timely and relevant research, and how doing so could improve the impact of research translation.

More work is needed to study other types of science policy efforts. Most research translation initiatives have too little data to evaluate their impact.

It is also worth considering the possibility that some efforts may unintentionally damage these political relationships and the credibility of scientific institutions. For example, partisan efforts that promote specific political agendas may reduce the perceived credibility of academic scientists.

And if educational outreach simply preaches science in the absence of interpersonal connections, academics not only risk perpetuating the stereotype of the disconnected and stubborn academy, they also risk wasting resources on ineffective programs, similar to the DARE program. original.

The bridge between science and politics is a two-way street. Not only must the parties meet in the middle, but science policy and communication practices must be held to the same rigorous standards we expect in evidence-based policymaking. The world needs solutions to countless crises in real time. How to forge these connections is itself a critical area of study.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization bringing you data and analysis to help you understand our complex world.

It was written by: Taylor Scott, State of Pennsylvania.

Read more:

Taylor Scott has received funding from the William T. Grant Foundation, the National Science Foundation Science Program, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the Penn State Social Sciences Research Institute and the Institutes Huck at Penn State. She directs the Research Translation Platform at Penn State’s Evidence to Impact Collaborative and serves on the boards of TrestleLink and the National Prevention Science Coalition.