Just before the Peking to Paris automobile race of 1907, The Economist – always prescient in its predictions – lambasted “those who had rushed with such unfortunate enthusiasm to invest in bus companies,” insisting that “the horse is outperforming triumphantly the test.” .

I owe this quote to Kassia St Clair’s charming new book, Race to the Future, which shows the way in which this strange collection of adventurers seized the public imagination, helping to transform the automobile from a mere experimental novelty to a mode of transportation for the mass market. that changed the world forever.

As Warren Buffet has observed about the advent of the automobile, it may not have been worth spending much time among the countless auto companies that sprang up at the time, the vast majority of which went bankrupt, but it certainly would have been wise to be short on horsepower.

To be fair to The Economist, it is very human nature to scoff at the impact of the new and, in fact, to resist its application altogether if given even the slightest chance.

“Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?” said Harry Warner, one of the founders of the Warner Brothers film studios, before rejecting proposals for films with sound in 1927.

In a similar vein, Lord Kelvin, president of the Royal Society, declared in 1895 that “heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible.” As for computers, don’t even start. “I think there is a world market for about five computers,” said Thomas Watson, president of IBM, in 1943.

Etc. In general, we tend to resist change, especially when it is imposed on us. Industry incumbents are even less likely to adopt it.

All of which brings us to the electric vehicle (EV). In the case of electric vehicles, we can be considerably more confident in our predictions, if only because governments around the world have ordered the end of the internal combustion engine. Whether we like it or not, it will be virtually impossible to buy a new fossil fuel-powered car within 10 to 15 years.

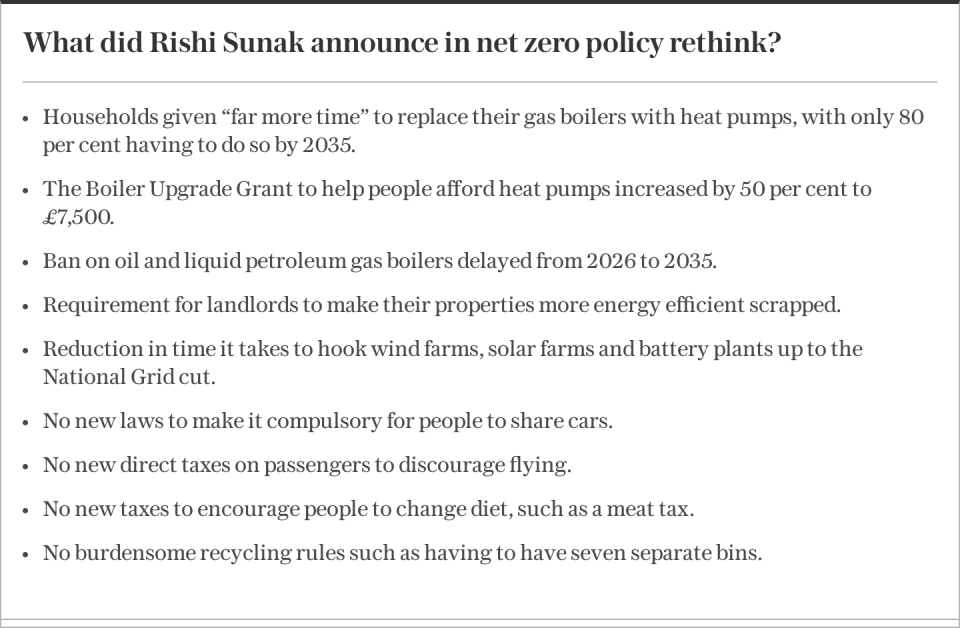

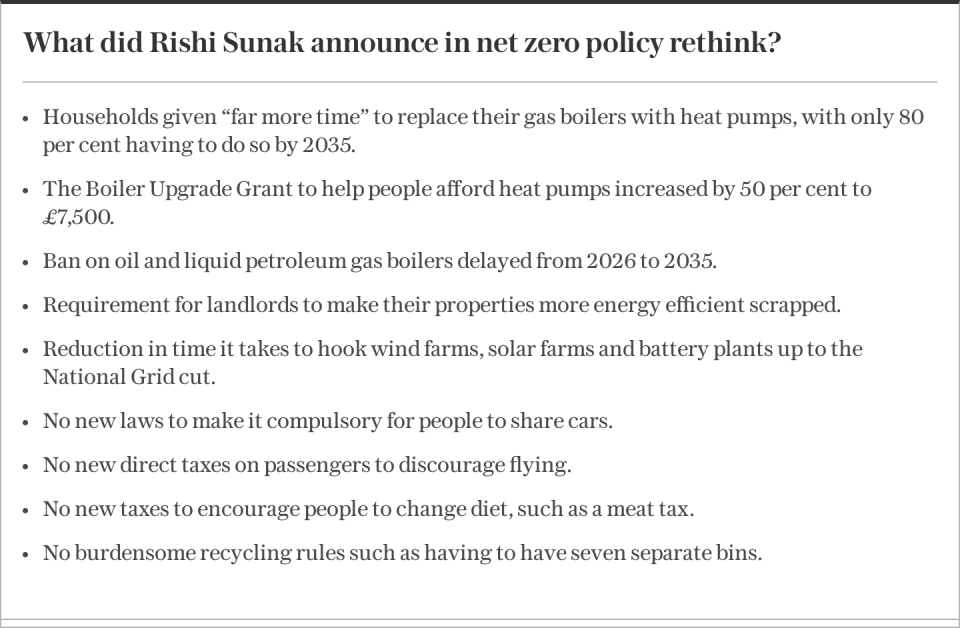

Downing Street likes to consider itself a friend of motorists: in an attempt to appease those who wouldn’t give up their trusty old vehicle for love or money, it recently pushed back the abolition date for the internal combustion engine by five years, to 2035.

This may make the transition path a little easier for some automakers, but overall, it won’t make much of a difference.

The so-called zero-emission vehicle mandate still requires 22 percent of all new cars sold in Britain next year to be zero-emission, rising to 80 percent by 2030. Make traditional cars that run on gasoline or diesel quickly It becomes uneconomical when limited to such a small proportion. From the market.

Therefore, any company that wants to stay in the game has to act quickly on the transition to electric vehicles, as Nissan declared it would do late last week with a heavily subsidized £2bn investment to make its plant of Sunderland to be fully electric by 2030.

This is obviously good news for the economy and rather puts an end to warnings that the forced march towards electric vehicles was the ultimate death knell for UK car manufacturing.

Nissan’s announcement follows BMW’s £600m investment in an electric Mini and Jaguar Land Rover’s plans for a £4bn gigawatt battery factory in Somerset.

Fears that increasing trade barriers with the European Union would cause all future investments in electric vehicles to be offshored to the continent are proving unfounded; The advantages of Britain’s flexible labor market appear to outweigh the rules of origin and other export market impediments that came with Brexit.

However, it remains true that to go a step further and gain mass market appeal, electric vehicles must become price competitive. As things stand, the infrastructure to support them is also woefully insufficient.

Tesla’s Model Y was Britain’s best-selling car in June this year, but with prices starting at around £45,000, it is still very much a product for wealthy enthusiasts only.

Surveys suggest there is a hardcore market of around 25 percent of households who are almost evangelical in their desire to own an electric vehicle.

At the other extreme, there are about another quarter of car owners who would under no circumstances buy an electric vehicle, although, unfortunately, it is possible to actuarially chart the likely future decline of this group of mainly elderly traditionalists.

For the average majority, the main deterrents lie in price and “range anxiety” – the fear that the car will not have enough battery to reach an available charging point.

In any case, after many years in which electric vehicle sales have consistently exceeded most expectations, the pace of growth has slowed noticeably, prompting the Office for Budget Responsibility to lower its forecast last week. of electric vehicle adoption from 67 percent of all new car sales in 2027 to 38 pieces.

The high initial cost of electric vehicles compared to vehicles powered by internal combustion engines is deterring many potential buyers, the OBR concluded, especially among those using car finance, which has become more expensive as a result. of the highest interest rates.

Charging at home can mean significantly lower running costs, but there’s little to no advantage to charging externally – and that’s if you can find a charging point in the first place.

Fears that the price of traditional vehicles is about to rise to help meet EV quotas further fuels the incentive to buy the old technology now, while you still can.

In other words, the transition will not occur as quickly as previously thought. Meanwhile, electric vehicles potentially pose a broader existential threat to the UK and European economies.

In planning to become the world’s largest auto supplier, China has largely skipped the fossil fuel development phase and gone straight to electric vehicles, some of which are already starting to become price competitive with the traditional European automobile industry and could therefore have a genuine mass. -market attractiveness.

Standing up to Chinese competition depends crucially on how quickly companies like Nissan can ramp up production to reduce unit costs. Technology is also changing at lightning speed. Solid-state batteries potentially offer manufacturers in the advanced world a real opportunity to get back on top.

The challenges existing manufacturers face in switching to electric powertrains are one thing, but the transition also poses a big problem for the Government, which currently rakes in around £25bn a year, equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP, of fuel taxes.

The last chancellor to propose road pricing as an alternative – Alistair Darling in 2005 – was sacked with a flea in his ear after an online poll suggested overwhelming opposition from motorists on privacy grounds alone.

However, the problem with charging the tax on the price of electricity is that it would penalize other uses of electricity. It would be difficult to differentiate. Furthermore, higher carbon taxes could only be a temporary solution.

No wonder ministers don’t like to talk about plugging the hole. However, decisions cannot be postponed forever.

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month, then enjoy 1 year for just $9 with our US-exclusive offer.