Subscribe to CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and more.

The disappearing “magic islands” on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, have intrigued scientists since NASA’s Cassini mission detected them during flybys a decade ago. Now, researchers believe they have revealed the secrets of the phenomenon.

These ephemeral features were initially thought to be formed by bubbles of bubbling gas, but astronomers now believe they may be honeycomb glaciers made of organic material falling onto the moon’s surface.

Scientists consider Titan one of the most fascinating moons in our solar system because it shares some similarities with Earth. However, in many ways it also presents a disconcerting alien landscape.

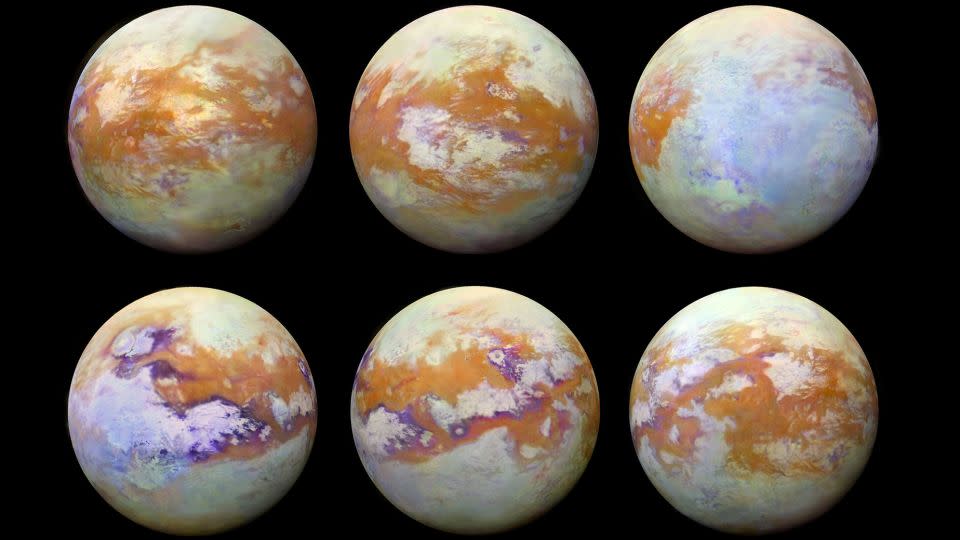

Titan, larger than our moon and the planet Mercury, is the only moon in our solar system with a thick atmosphere. The atmosphere is largely composed of nitrogen with a little methane, which gives Titan its fuzzy orange appearance. Titan’s atmospheric pressure is about 60% greater than Earth’s, so it exerts the kind of pressure humans feel when swimming about 50 feet (15 meters) below the ocean surface, according to NASA.

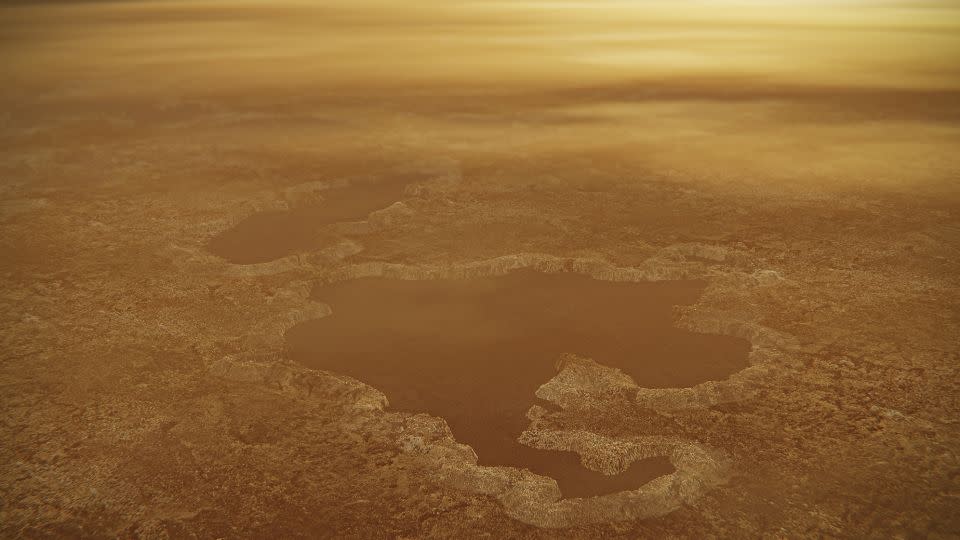

Titan is also the only other world in our solar system that has Earth-like liquid bodies on its surface, but the rivers, lakes and seas are composed of liquid ethane and methane, which form clouds and cause liquid gas to rain from the sky. . .

The Cassini mission orbiter, carrying the Huygens probe that landed on Titan in 2005, performed more than 100 flybys of Titan between 2004 and 2017 to reveal much of what scientists know about the moon today.

Among the most puzzling aspects of Titan are its magical islands, observed by scientists as moving bright spots on Titan’s sea surface that can last a few hours, several weeks, or longer. Cassini radar images captured the unexplained bright regions of Ligeia Mare, the second largest liquid body on Titan’s surface. The sea is 50% larger than Lake Superior and is made up of liquid methane, ethane and nitrogen.

Astronomers thought these regions could be clustered bubbles of nitrogen gas, actual islands made of floating solids, or features attributed to waves (although the waves only reach a few millimeters in height).

Planetary scientist Xinting Yu, assistant professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio, focused on analyzing the connections between Titan’s atmosphere, liquid bodies and solid materials that fall as snow to see if they could be related to the magical islands. .

“I wanted to investigate whether magic islands could actually be organic matter floating on the surface, like pumice that can float in water here on Earth before eventually sinking,” said Yu, lead author of a study published Jan. 4. in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. .

Scientists aim to understand everything they can about Titan before sending a dedicated mission to the moon. The Dragonfly mission, led by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in partnership with NASA, is expected to launch in 2028 and reach Titan in the 2030s.

Analyzing an unusual world

A wide range of organic molecules exist in Titan’s upper atmosphere, including nitriles, hydrocarbons, and benzene. The surface temperature is so cold, -290 degrees Fahrenheit (-179 degrees Celsius), that rivers and lakes were carved by liquid methane, just as rocks and lava helped form shapes and channels in the Land.

Organic molecules in Titan’s atmosphere stick together into clumps before freezing and falling to the moon’s surface. Dark plains and dunes of organic material have been observed on Titan, and scientists believe the features were largely created by Titan’s “snow.”

But what happens when hydrocarbon snow falls on the eerily smooth surfaces of Titan’s lakes and rivers of liquid gas? Yu and her colleagues investigated the different scenarios that could occur.

Yu’s team determined that solid organic material falling from the upper atmosphere would not dissolve when it landed in Titan’s liquid bodies because they are already saturated with organic particles.

“In order for us to see the magical islands, they can’t just float for a second and then sink,” Yu said. “They have to float for a while, but not forever either.”

But liquid ethane and methane have low surface tension, meaning it’s harder for solids to float on top of them.

Yu’s team simulated different models and determined that frozen solid material would not float unless it was porous, like honeycomb or Swiss cheese. Small particles are also unlikely to float on their own unless they are large enough.

The team’s analysis resulted in a scenario in which frozen hydrocarbon solids clump near the coast, then break up and float to the surface like Earth’s glaciers. Liquid methane slowly seeps into the frozen clumps, eventually causing them to disappear from view.

Additionally, according to the researchers, a possible thin layer of frozen solids in Titan’s seas and lakes may explain why the moon’s liquid bodies are so soft.

Approaching Titan

In the next decade, Dragonfly is expected to largely investigate the plains of organic material in Titan’s equatorial region, rather than its liquid bodies.

The helicopter lander will sample materials on Titan’s surface, study the potential habitability of its unique environments, and determine what chemical processes are taking place on the moon.

Organic chemicals essential for life on Earth, such as nitrogen, oxygen and other carbon-based molecules, are also found on Titan. Beneath Titan’s thick crust, made of ice, is an internal ocean of salt water, not unlike other fascinating moons of the ocean world orbiting Saturn, such as Enceladus or Jupiter’s moon Europa, which are some considered one of the best places to look for life beyond Earth.

Titan sounds inhospitable, but it’s possible that conditions there could be conducive to life depending on different chemistries and shapes in ways that are beyond our current understanding, according to NASA.

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com