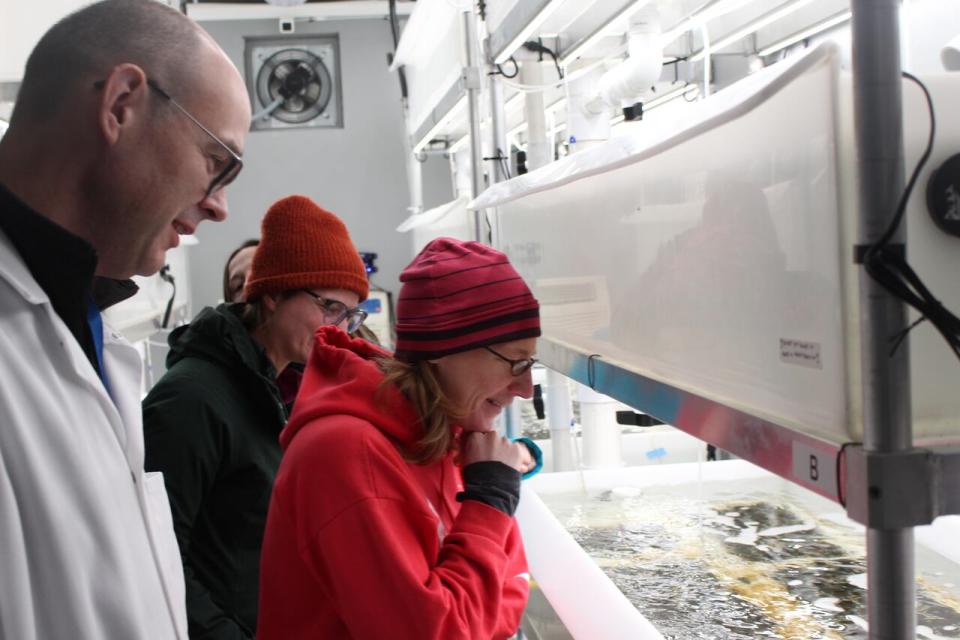

In a converted shipping container by the sea in Ketch Harbor, N.S., a group of people gather to peer into tanks filled with blurry chunks of gravel.

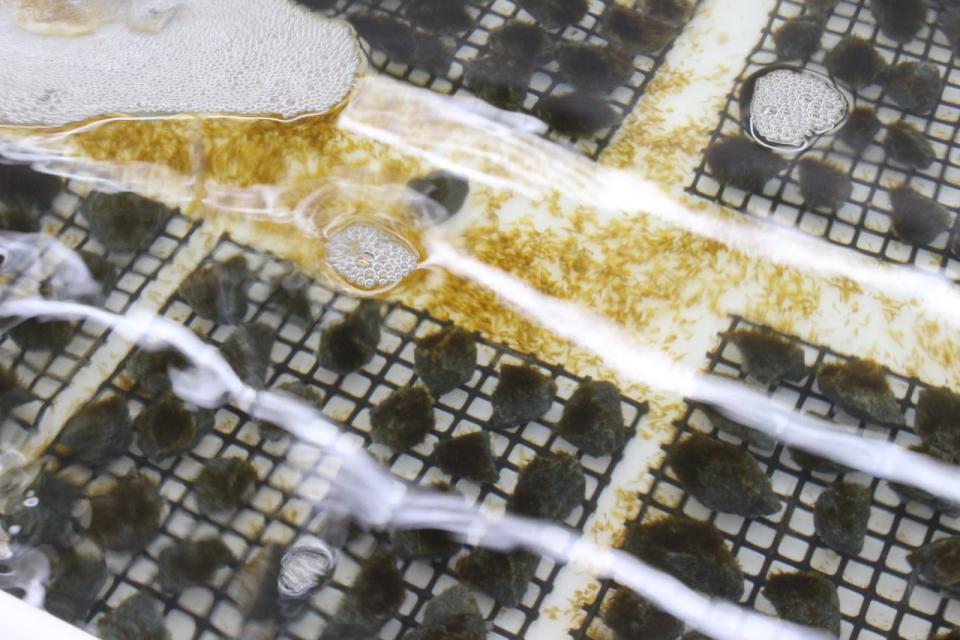

The rocks are covered with tiny sheets of sugar algae. Soon, the squares of steel mesh to which they are attached will be suspended in the water at a seaweed farming demonstration site in Mahone Bay, in hopes of safeguarding Nova Scotia’s future seaweed beds.

It’s an effort by scientists, conservationists and a West Coast company working together on the restoration technique for the first time in Nova Scotia, although it is used in other parts of the world.

Kelp is a crucial part of Nova Scotia’s marine environment, providing habitat for a variety of other species and removing excess nutrients from the water. But due to rising water temperatures, habitat destruction and pollution, algal beds are declining, with consequences for ecosystems.

“We have kelp beds on both coasts that are shrinking, or maybe even being lost completely,” said Stephen O’Leary, research team leader at the National Research Council. But with green gravel technology, scientists hope they can give seaweed in Nova Scotia and beyond a better chance at long-term survival.

Participants in the green gravel project inspect the algae in the mobile laboratory. (Moira Donovan)

The project involves collecting seaweed sheets from Mahone Bay in the fall, when decreased daylight and colder water temperatures cause the algae to enter a reproductive state, collecting microscopic spores from the reproductive sheets and use those spores to “inoculate” the rocks. In other words, causing the spores to settle in the gravel.

Shipping container is mobile

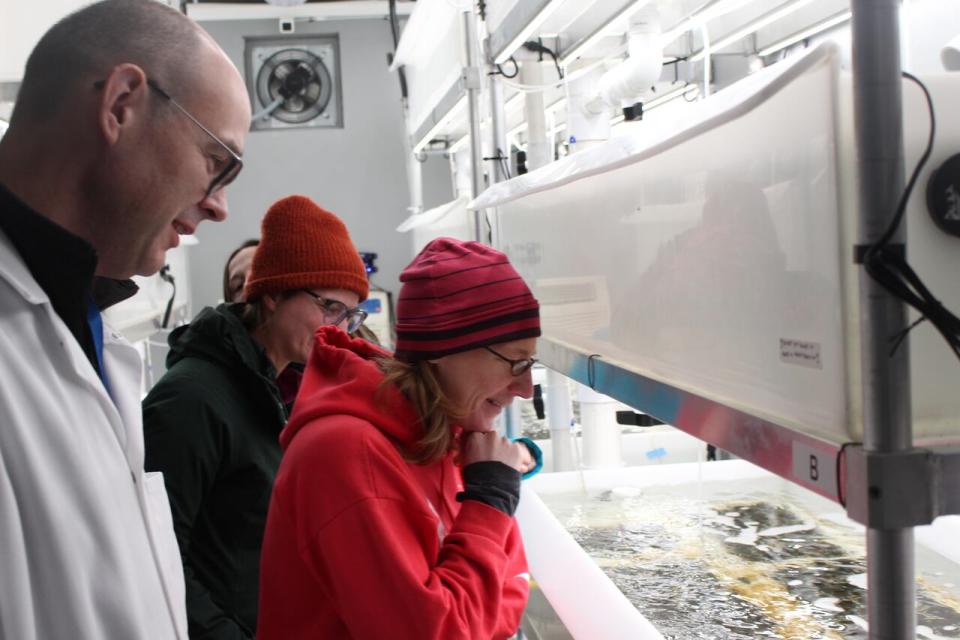

Those tiny spores were then grown to a sufficient size to be planted in a specially designed shipping container created by Cascadia Seaweed based on Vancouver Island in British Columbia. The mobile lab was designed specifically to produce green gravel and has been tested at the National Research Council’s Ketch Harbor facility, but could ultimately be moved to any location where green gravel is being developed and deployed.

The green gravel test was also a demonstration of Cascadia Seaweed’s mobile laboratory, which is designed to be moved to any seaside location where needed. (Moira Donovan)

During its first test, O’Leary said scientists were initially unsure if the experiment had worked.

“For three weeks it seemed like we only had tanks for gravel and it wasn’t clear if anything was growing in them or not,” he said. “So we thought: Are we growing gravel here or are we growing algae?”

Then, after a weekend in early December, the scientists returned and found the gravel covered in tiny sheets of seaweed.

Typically, the gravel would then be spread into the ocean, where it would settle to the sea floor. One or two of the many small sheets of algae covering the rocks would survive to grow to three meters in length, and the base of the algae, called a hold, would grow around the rock to adhere to the bottom.

In this case, the rocks are attached to 110 squares of steel mesh that will be suspended several meters deep in the water column, so researchers can track how well the algae grow using this method. Then the algae will grow from December to May.

Landscaping gravel is “inoculated” with algae by placing gravel in tanks with microscopic algae spores that then attach to rocks and grow up to half a centimeter in size before being dumped into the ocean. (Moira Donovan)

“We do not expect to restore a kelp bed in Mahone Bay at this time, but we are developing the techniques and technologies that would allow us to make that restoration application at a later date,” O’Leary said.

This technology has implications beyond Mahone Bay.

Flora Salvo is an industrial researcher at the Merinov research group in Quebec, which is also participating in the project. She said they are thinking about doing something similar in Quebec.

Merinov is also working with the National Research Council to build an algae seed bank. Combining the supply of genetic material from it with the green gravel technique could allow the repopulation of areas where algae have been degraded or disappeared due to pollution and higher temperatures.

A pilot project for seaweed cultivation is underway in Mahone Bay, NS. A new report suggests the industry could be worth almost $40 million in Nova Scotia within three to five years. (Ecological Action Center)

“So having this seed bank ready could [make it] easy for people who will do marine afforestation, using marine gravel technology,” Salvo said.

Over time, this could mean replanting areas using spores from individual kelp plants that have been identified as naturally resistant to changing conditions, such as warmer waters.

Meanwhile, scientists say having baseline data on the green gravel technique and its effectiveness, as well as more biological data on algae, could inform restoration regulations. At the moment, there are no regulations for seaweed restoration in the Atlantic provinces.

Restoration for the right reasons

Shannon Arnold, associate director of marine programs at the Halifax Ecological Action Centre, said that as scientific attention and investment in seaweed restoration increases, guidelines are needed.

By participating in green gravel research, including offering the EAC’s seaweed farming demonstration site in Mahone Bay as a site for the experiment, Arnold said they can help answer basic scientific questions that inform this process.

“In Canada right now… we don’t have really strong safety barriers or guidance on best practices for restoration,” Arnold said. “That’s something we’re going to work on with other groups to see what we need to guide these types of things.”

Arnold said the hope is that the involvement of different groups in the green gravel project will help develop restoration practices that make a positive difference, including recognizing that the best way to ensure the long-term future of algae is not through restoration, but by addressing the underlying reasons for the decline of seaweed.

“Our main goal should always be: protect first, then manage, and then the last opportunity is restoration, because restoration is very difficult to achieve,” he said. “We want to make sure we’re doing restoration for the right reasons and in the right places.”

MORE TOP STORIES