Editor’s Note: Call to Earth is a CNN editorial series committed to reporting on the environmental challenges facing our planet, along with the solutions. Rolex’s Perpetual Planet initiative has partnered with CNN to raise awareness and education on key sustainability issues and inspire positive action.

A storm of starlings, rising from the reeds and wetlands of southern Denmark, rains down on the horizon. The group of birds looks like drops of ink on a parchment canvas, spread across a dark sky where they dip and spin in unison. The birds fold like waves on the shoreline, contorting into abstract formations that loom over the marshes.

The phenomenon, known as starling murmuration in English or “black sun” in Danish, lasts just a few minutes or even seconds. But it left a lasting impression on Danish photographer Søren Solkær, who first witnessed the spectacle when he was 10 years old.

“At that time it was by far the wildest thing I had ever seen in my life,” Solkær recalls.

Over the next 40 years, Solkær built a career as a portrait photographer, traveling the world to take iconic images of the world’s biggest rock stars: Amy Winehouse, Metallica, Paul McCartney and Led Zeppelin, to name a few. But during a career retrospective of his in 2017, Solkær was inspired to try something new.

“The first thing that came to mind was the murmurations of starlings… this big piece of calligraphy in the sky,” he told CNN. He began photographing the birds near his childhood home in southern Denmark, before following several flocks across Europe, from Ireland to Italy, on his migratory route.

Solkær’s latest photobook, “Starling,” published last month, traces this migratory journey and, with it, hopes to inspire a closer relationship with nature.

“One of the reasons it continues to captivate me is that every time it happens, it’s new, it’s unique. Shapes appearing in the sky occur only once in the history of the world,” he said. “I think that’s a very good reason to photograph them and try to capture them and share them with others.”

A spectacle at sunset

Solkær first published images of starlings in his 2020 photobook “Black Sun,” describing it as “an investigation of where I come from and how to deal with those childhood memories.” After several seasons of photographing birds near the Wadden Sea in Denmark and neighboring countries, Solkær decided to expand the scope of the project and follow the birds as they migrate across the continent.

European starlings can migrate as far as the Arctic Circle in summer and as far as North Africa in winter. It is during these migrations that murmurations are most common, although the exact reason behind them remains a mystery: a widely accepted theory is that starlings gather in these dense aerial formations before dusk to appear larger to predators. But scientists also suspect it may attract other starlings to the roost and generate heat in cold winters.

Using Instagram hashtags to locate where the murmurations were occurring, Solkær chose his destinations based on the size of the flock and the presence of predators, such as peregrine falcons, since starlings adopt the “most beautiful graphic shapes” when under attack. But even with the best-laid plans, nature is unpredictable.

“It’s very ephemeral: you can get five good photographs in half a minute, but then nothing for the next six weeks,” Solkær said. “It doesn’t happen every night. “The really amazing formations usually occur once or twice during the winter.”

One of the largest winter populations is located in Rome, Italy. The cityscape, as well as the southern evening light, contrasted sharply with Solkær’s work in the Danish marshes.

“It’s the same phenomenon, but the light is much more golden and the sky is very beautiful,” Solkær explained. While many of his previous shots of the murmurations used a monochromatic aesthetic, he began playing with color, as well as including architecture in some images.

Rome also provided the perfect backdrop for Solkær to explore the relationship between wild and urban environments, through the city’s difficult relationship with starlings.

“Rome spends a lot of money trying to scare the birds out of the city, because they make a big mess,” he said, adding that the city hired a falconer to scare away the starlings.

However, starlings have been a fixture in Rome since ancient times. “They used to think that the shapes and behavior of starlings were gods trying to communicate with humans,” Solkær explained. Fortune tellers read auspicious signs or bad omens that influenced political decisions. Solkær builds on this story of mysticism, capturing a sense of wonder with fantastical formations framed above the spiers of ancient architecture against a backdrop of cotton candy pastel clouds.

“It’s a very different experience than standing in a field in the middle of nowhere. But I think it’s equally magical; It seems even more surreal when you’re in the city and see the same thing happening. It doesn’t fit very well and that’s also what’s causing the big fight between the city of Rome and the birds,” Solkær said.

From the macro to the micro

While starlings are often thought of as a common bird in Europe and North America, their numbers have been declining for decades (they fell by 53% between 1995 and 2018) and in the UK they are on the Red List of threatened species. .

“There are far fewer birds now than before,” Solkær said, pointing to the increasing use of land for agriculture, which has reduced food availability.

After the success of “Black Sun,” many biologists and ornithologists approached Solkær, inspiring him to not only look at starlings from afar, but also up close.

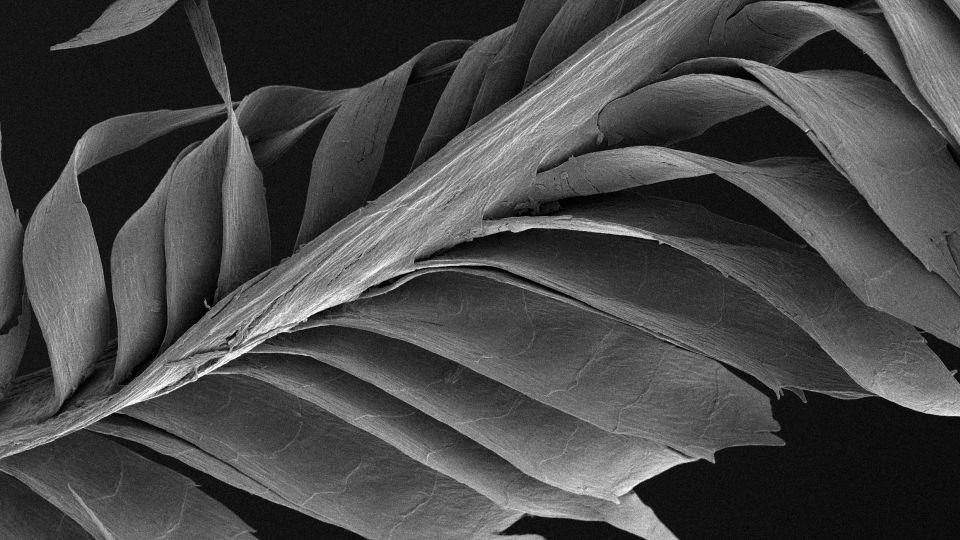

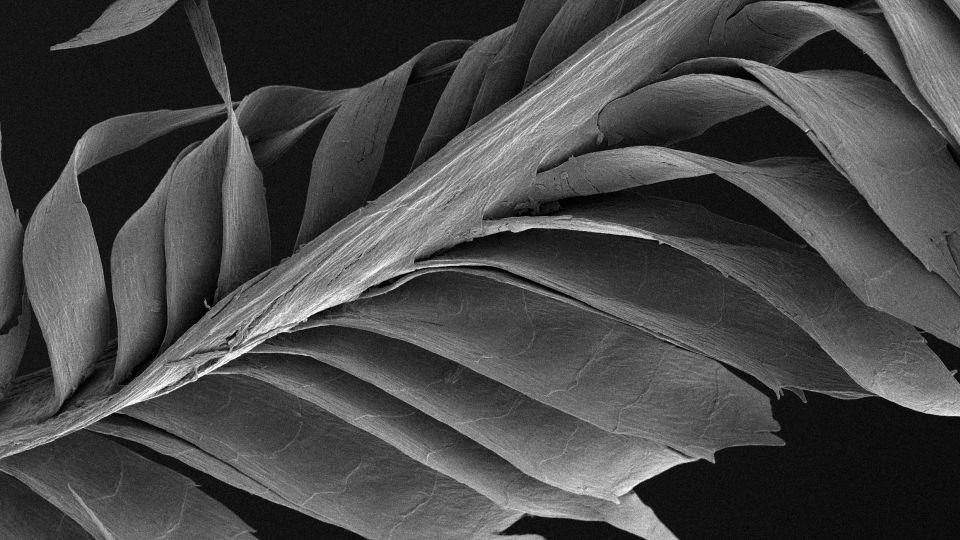

In collaboration with the University of Copenhagen, he produced two series of images taken with microscopes.

“They have really beautiful metallic feathers when you see them up close,” Solkær said. “I’ve tried to go from the big macro world I’ve seen in the sky to see if I could find some of the same universal patterns if I got really, really close.”

An ornithologist, an octogenarian professor at the Natural History Museum, provided Solkær with a taxidermied starling from the museum’s collection to photograph.

“I could see from the small tag attached to his paw that he had died in 1918 when he crashed into a lighthouse, (but still) he looked perfect,” Solkær said.

He photographed the bird under optical and electron microscopes, magnifying the starling up to 12,000 times. The detailed images show the dense but delicate strands of feathers, which resemble the outlines of a map, palm leaves and tree trunks, providing a striking contrast to his shots of outdoor murmurations.

“The closer I got, the bigger it seemed, like mountains and river deltas,” Solkær said.

The project has sparked Solkær’s interest in other conservation photography projects. She is now embarking on a project about dragon trees, a rare species endemic to the island of Socotra in the Indian Ocean, as well as a book about spirituality and nature in Bhutan, South Asia.

“At this point, at least for me, it doesn’t make sense to focus on rock stars,” he said. “I think it is very necessary to communicate these stories now and inspire a closer connection with nature.”

As for birds, Solkær is considering other species for possible projects: the sandpiper, for example, a gray bird with a white belly that performs an aerial dance similar to that of starlings; or the screeching green parakeets of Australia, which contrast sharply with the red rocks of the interior and the extensive blue sky.

“I don’t think I’ll do another book about starlings,” Solkær said. But he pauses and collects himself: “Actually, I think that in 10 days I will go to Sardinia to photograph starlings. Then, who knows?”

Videos courtesy of Søren Solkær.

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com